Configuring a 'Newer Malaysia'

By Meredith L Weiss, Professor and Chair of Political Science, Rockefeller College of Public Affairs & Policy at the University at Albany, State University of New York

The seeds of the present meltdown germinated a long while back: these include accelerating shifts in Malaysian political parties in recent years, the still-central place of personalities in Malaysian politics, and the tenuousness of Pakatan Harapan’s (PH) initial win in 2018.

Malaysia’s party system sets it apart within Southeast Asia. Unlike in Indonesia, the Philippines, or Thailand, Malaysian political parties are coherent, enduring, distinct, and allowed to contest. Unlike in Singapore, most identify with defined, commonly ethno-religious, constituencies rather than taking a catch-all approach, and compete and even register legally qua pre-election coalitions. And yet these parties are prone to fracture, especially under the weight of heavy egos; that process in particular yields parties that compete in similar terms for the same base (consider UMNO, PPBM, and PAS within the new government), rather than for complementary subsets. Such problems have grown more cumbersome given leaders entrenched for decades, shutting out internal challengers, and as economic restructuring, including through affirmative action, has forged an increasingly urban, multiracial middle class. By now, many communal concerns have lost the coincidence with class and occupational position of days past, leaving parties pressed for new ways to differentiate their appeals. To say a party is “Malay” in focus or constituency tells us comparatively little about its specific priorities and positioning, especially vis-à-vis an increasingly crowded field of “Malay” parties.

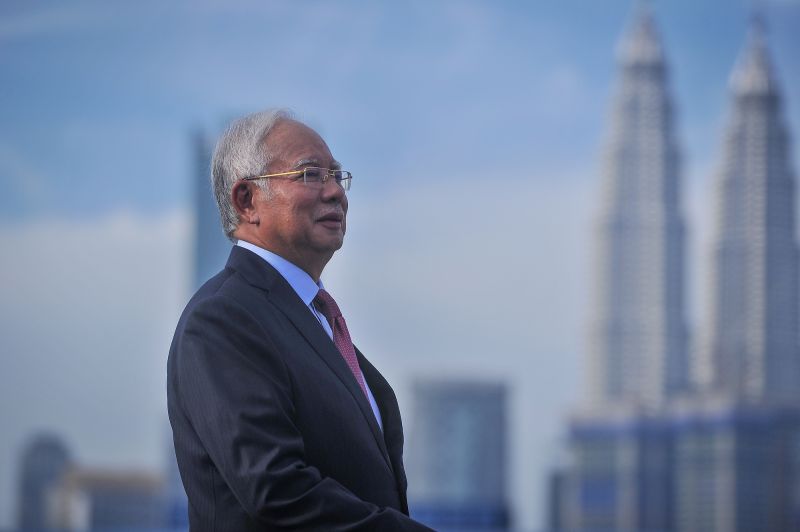

Former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak attending the 2018 Police Day Parade, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia - March 25, 2018. Image: Izzuddin Abd Radzak, Shutterstock.

Weakening this system all the more was the shift from Pakatan Rakyat to Pakatan Harapan in 2017 – specifically, the addition of Malay-communal PPBM to a formally (even if clearly not entirely) non-communal alliance, since it left neither coalition with a clear programmatic compass (beyond being for or against Prime Minister Najib Razak’s continued leadership).

Mahathir’s call in the midst of the recent political turbulence for a “unity government” not of parties per se, but of worthy people, represents an especially cynical take on the capacity of parties to channel popular interests, elevate competent leaders, eschew rent-seeking, and negotiate effectively. We might expect longer-term implications for weakening party unity, as what had been identity-based or ideological parties veer ever closer to being only distinguishable by their leaders.

One cannot think through these issues of hollowed-out, brittle parties without acknowledging the extent to which the “personal touch” cements a personal vote for most Malaysian politicians. Charisma and personal patronage have always loomed large in Malaysian politics, to the extent that personalities have eroded their parties, shifting debates to questions of who, not what ideas or programs, define the party.

Were Mahathir, Anwar Ibrahim, Azmin Ali, and their respective acolytes not all equally certain of being Malaysia’s one rightful political saviour, or had they put their party’s future above their own, Anwar’s and Azmin’s Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) and PH would not have been so obviously teetering, nor would speculation have leapt so promptly and plausibly to whose power-play these events really represented. Whatever other fissures erupted, Anwar’s insistence on his turn as prime minister, Mahathir’s reluctance to step aside, and Azmin’s strategic spoilership all put personal interests above programmatic objectives – and opened the door for Muhyiddin Yassin to trump all three rivals.

PKR President Anwar Ibrahim speaking to media in Port Dickson, Malaysia - July 20, 2019. Image: Shafwon Zaidon, Shutterstock.

Finally, there is the well-known reality that PH and PAS kept Barisan Nasional from winning in 2018 thanks at least as much to a protest vote against Najib Razak as a proactive vote for reform. The Malay vote in particular split three ways – PH, PAS, UMNO – in GE14; PH’s support was always higher among non-Malays. Amanah still has yet to cultivate strong grassroots support, and while PPBM lured a share of Malay voters, the party fit awkwardly with the coalition and coasted on support for Mahathir. Since the elections, PH’s popularity had declined dramatically; confidence levels rivalled Najib’s pre-election lows.

Even before UMNO and PAS moved to cement their Muafakat Nasional, precursor to the current coalition, in 2019, ethno-religious grandstanding offered a bludgeon against both a range of proposed PH reforms (e.g., Malaysia’s signing on to the UN’s ICERD) and steps toward racial inclusivity, particularly Mahathir’s appointment of non-Malays to several key government posts. That a Malay base could be so readily galvanised against PH and its plans boded ill for the coalition’s longer-term viability.

What next?

The new Perikatan Nasional (National Alliance, PN) + Gabungan Parti Sarawak (Coalition of Sarawak Parties, GPS) government has yet to present a platform or policy agenda, beyond the largely symbolic premise of further advancing the interests of Malays and Islam. The coalition reflects power struggles and politicians’ quest for power, not an ideological or programmatic consensus. In fact, it is not obvious what this administration will prioritise, or how it will navigate real differences and competing claims among component parties. UMNO, PAS, and PPBM have overlapping catchments. The former two parties already knew sharing out seats and executive roles for GE15 would be challenging, but at least PAS and UMNO are strong in different states. Now those tensions are immediate, with ministries (and policies) on the line. What follows is not a definitive reading of what lies ahead, but more suggestions of likely pressure-points, looking first to the institutional landscape, next to partisan dynamics, and finally, to civil society.

Institutional landscape

First, institutions. At the most macro level, the implications of current developments for centre-periphery relations, looking across tiers of government, are particularly hard to parse. State-level dynamics are, if anything, even more convoluted than those at the federal level. Malaysia’s federation is extraordinarily centralised – and local-government elections are surely off the table now, notwithstanding the reappointment of Zuraida Kamaruddin as Minister of Housing and Local Government. (Even under PH, and with Zuraida’s backing, the odds of their introduction, at least beyond a test-case or two, were about even.) Since 2008, Malaysia has had a cluster of states under federal-opposition rule; since 2018, that picture has been even more mottled. Now we have fractured parties that align in different ways, coupled with a strong likelihood that PN will revert to the BN mode (which even PH failed to doff entirely) of penalising not just opposition MPs, but also state governments outside their camp. Meanwhile, PN’s East Malaysian partners remain kingmakers – albeit now sharing that privileged status with each other component equally necessary to Muhyiddin’s majority – by embracing their peripheral status. Their states’ quest for rights and at least their fair share of benefits recommends that parties from Sabah and Sarawak specifically not seek closer integration into a Malaysian whole or more reliable ties with any given “Malayan” party.

Former Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad campaigning on May 3, 2018. Image: Kean Wong

More broadly, PN’s reformist inclinations seem likely weak, although electoral pressures (more on those below) may well push contenders for PN leadership to champion certain aspects of a reform agenda. PH had made only limited progress toward its promised institutional-reform efforts. Still, those changes already achieved (expanding the franchise, introducing parliamentary select committees, improving election administration, relaxing restrictions on undergraduates’ political activities, professionalizing the foreign service, etc.) stand a good chance of remaining in place.

Anti-corruption reforms specifically may fare less well. Even if the cases against those UMNO members facing 1MDB-related or other corruption charges continue and result in conviction – an outcome not at all certain – UMNO, at least, gives no indication of prioritising better governance. The party re-embraced its old guard post-GE14, and several of those charged now seem poised for full political revivification. UMNO can see no institutional advantage in spotlighting corruption at this point, although party secretary-general Annuar Musa has warned against PN’s pressing the courts to drop any cases but those politically motivated. (He did not specify criteria for that determination.) For their part, PPBM and PAS may hesitate to draw attention to their now partnering with politicians they so recently excoriated for extreme rent-seeking. Moreover, although Mahathir had prioritised anti-corruption reforms from the outset of PH’s brief reign, much of that revamped apparatus relies on key individuals who may no longer be players. That his Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission chief, long-time activist Latheefa Koya, resigned the day after Muhyiddin’s swearing-in is hardly propitious. On the other hand, now that PAS has worked its way into the federal government for the first time in over 40 years, the party may find itself able (or compelled, however usually loyal its voters) to stand on principle and insist that 1MDB investigations continue – a requirement UMNO would surely resist.

Beyond these institutional arrangements, PN will surely seek to distinguish itself from both PH and, to some extent, the BN. Central to that effort will likely be aggressive statements and actions to assert Malay-Muslim centrality – and policies to support such icons of Malay-Muslimhood as farmers and civil servants. PH’s Shared Prosperity Vision (SPV) 2030 plan and budgets also included safety-net spending for the mostly-Bumiputera “B40” (socioeconomic bottom 40 per cent) and ultimately embraced a not-so-different race-based frame. Indeed, Muhyiddin quickly announced that SPV 2030 will continue. However, these initiatives – as well as a stimulus package about to be rolled out to counter the COVID-19 downturn – notes Tricia Yeoh, may have been “too little, too late” for PH.

Vandalised campaign materials on a roadside in Johor, Malaysia - April 30, 2018. Image: Kean Wong.

Especially dicey for PN will be embracing its Malay-centrism without, on the one hand, entirely alienating the non-Bumiputera nearly one-third of the population, and on the other hand, competing most heatedly among themselves for the Malay vote. PAS, for instance, is perennially at pains to insist that they are not anti-Chinese, merely anti-DAP; despite no longer emphasising its earlier “PAS for All” mantra, the party frames racial tolerance as necessary for legitimacy. Yet the substance of the critique PAS and its now-partners offer is racial: that in sharing power meaningfully, Chinese Malaysians usurp the rightful prerogative of Malays. (Common discourse of Islam’s being under siege supplements that ethnic claim, but with scant evidence.) PAS president Hadi Awang has insisted that only Muslims may govern Muslims, a stance at odds with recognising equal political rights for all citizens. Now PN, and specifically PAS, may confront an electoral incentive to moderate their approach. Focusing on non-zero-sum policies rather than ethnonationalist showboating may, for instance, stem further non-Malay-Muslim brain-drain at an economic crunch-time – less an issue for PAS’s state government in overwhelmingly Malay Kelantan than nationally.

At the same time, PN’s primary justification is the need to restore and enhance the status and prerogatives of Malays and Islam in Malaysia. That the bloated 70-member cabinet includes only 5 Chinese and 2 Indian representatives is testament to the ethno-nationalist impulse – even if East Malaysian Bumiputera, at least, are better represented than in the past (including with a designated ministry). Yet UMNO, Bersatu, and PAS all fish in the same vote-pool (as does PKR, too, to a significant extent). These parties may be under pressure to “out-Malay” one another in the quest for identitarian votes … but again, doing so, may compromise their ability to lure the non-Malay votes that could well tip the scales to their advantage. Given Malaysia’s unusually fragmented parties now, in other words, a “Malay unity” government may be both disunified in logistically challenging ways and pressed to curry favour with non-Malays.

Complicating the picture are personalities: more than one PN leader sees a path to the premiership. Especially worth watching is the potential tussle (implicit if not explicit) between UMNO’s Hishamuddin Hussein and Bersatu’s Azmin Ali (late of PKR). Should an acquitted Zahid re-enter the picture, perhaps as deputy prime minister (a post Muhyiddin has thus far declined to fill), sparks may well fly. Perhaps the best hope for racially inclusive and/or otherwise “progressive” institutional or other reforms, moving forward, is the contest to succeed Muhyiddin. With all contenders’ laying claim to the Malay vote, one or more may seek to expand their catchment via serious outreach to non-Malays, and each may distinguish himself (the PM shortlist is likely to be all-male, in this coalition) not just via comparatively more “conservative” (probably Islamist) policy agendas, but also by “liberal” ones.

Civil society

What sort of engagement the new government will encourage or allow, and how energetic civil society organisations (CSOs) of varying stripes are inclined to be, is especially dubious. That PN immediately moved to investigate over 20 activists for demonstrating against its “backdoor government” suggests the improvements to civil liberties PH had promised may get the axe. That likelihood makes it all the more unfortunate that PH did not push harder for those reforms when it had the chance. (Between the overwhelmingly male phalanx of politicians in PN’s media coverage and cabinet, and the fact that several smart, critical women are among the first to be investigated, we should likely not expect great strides for women, either.) All-but-certain rhetorical and real assertions of Islamism ahead, to affirm PN’s more-Islamist-than-PH credentials, may well chip away, too, at the already curbed freedoms of religion and expression Muslims and non-Muslims alike enjoy – and could well prove devastating for the already beleaguered LGBT minority in particular.

Rainbow flag appearing at the 2019 Malaysian Women's March, organised in conjunction with International Women's Day, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia - March 22, 2019. Image: Izzuddin Abd Radzak, Shutterstock.

It has been from progressive segments of Malaysian civil society that the most urgent and consistent pressure for rights protections has come thus far. That so many of those activists and organisations rallied and coordinated to press their case with and through PH, though, seeing an opportunity, may make it harder for them to regroup and re-energise, moving forward. Civil society can still remain an effective space for mobilization and voice, but the risks of crackdown, not to mention sheer enervation, are high.

And there may well be an enduring normative legacy to the unconventional way this government formed. Among the few institutional changes not readily reversed is Malaysia’s first-ever bipartisan constitutional amendment, lowering the voting age from 21 to 18, a change from which all parties presumably thought they stood to benefit most. Voters new to the scene, without broader or longer-term perspective, might be especially likely to perceive electoral democracy as decidedly perverse: if the losers dislike the outcome, they can flip the tables and declare a win, sidestepping the voting public. One can hardly help but wonder, too, whether the Agong, Malaysia’s king, may have raised doubts about the monarchy’s political legitimacy by taking it upon himself to resolve a partisan impasse – not least given the secrecy of tally and seeming skew to his decision at the time. (In the Agong’s defense, Malaysia’s king does have a larger role than in other constitutional monarchies, including in executive appointments.)

In other words, the short-term costs of the PH government’s collapse and the PN government’s rise are readily totted up in terms of institutional reforms and political house-cleaning foregone, likely investments diverted, and general frustration; the longer-term costs could be citizen disillusionment and disengagement, should votes seem not to matter and other institutional checks to be ineffective. Nor is there reason to expect lack of confidence in political institutions and processes to be limited to PH supporters: the twists and turns of recent weeks, and the production of political outcomes through elected and hereditary elites’ say-so, is profoundly disempowering, even for the winners of this round.

Muhyiddin’s majority is precarious, relations among parties in his coalition are fraught, and the fragile Malaysian economy offers little room for the new government to spend its way out of a corner. Plot threads and protagonists remain hanging; it may be some time yet before Malaysian politics finds its new “normal.”

Meredith Weiss is Professor and Chair of Political Science in the Rockefeller College of Public Affairs & Policy at the University at Albany, State University of New York. Meredith has published widely on political mobilisation and contention, the politics of identity and development, and electoral politics in Southeast Asia, with particular focus on Malaysia and Singapore. Her books include Student Activism in Malaysia: Crucible, Mirror, Sideshow (Cornell SEAP, 2011), Protest and Possibilities: Civil Society and Coalitions for Political Change in Malaysia (Stanford, 2006), The Roots of Resilience: Authoritarian Acculturation in Malaysia and Singapore (Cornell), as well as a number of edited volumes. She co-edits the Cambridge University Press Elements series on Southeast Asian Politics and Society.

Rebirth: Reforms, Resistance and Hope in New Malaysia is now available. To purchase a copy in Australia, email rebirth2020@protonmail.com.