Korea’s cultural exports and soft power: Understanding the true scale of this trend

By Jimmyn Parc, Associate Professor, Department of East Asian Studies – University of Malaya

When it comes to news articles on South Korea, the international press tends to focus on three topics: inter-Korean relations, economic issues, and Korean popular culture. Although each is a worthy topic, popular culture has drawn much interest recently due to the high global demand for Korean popular music (or K-pop), dramas, and films. Examples include the supergroup BTS, the Netflix hit series Squid Game (2021), and the Oscar-winning film Parasite (2019).

This global impact of Korean popular culture is referred to as Hallyu or the ‘Korean Wave’. Interestingly, when the concept of Hallyu became widely known in the 2000s, some observers were skeptical, arguing that in the long run demand for Korean popular culture could not be sustained. Despite the pessimistic forecasts, the scope of Korean popular culture has diversified, while its geographical coverage has expanded significantly, in turn enhancing Korean soft power around the world.

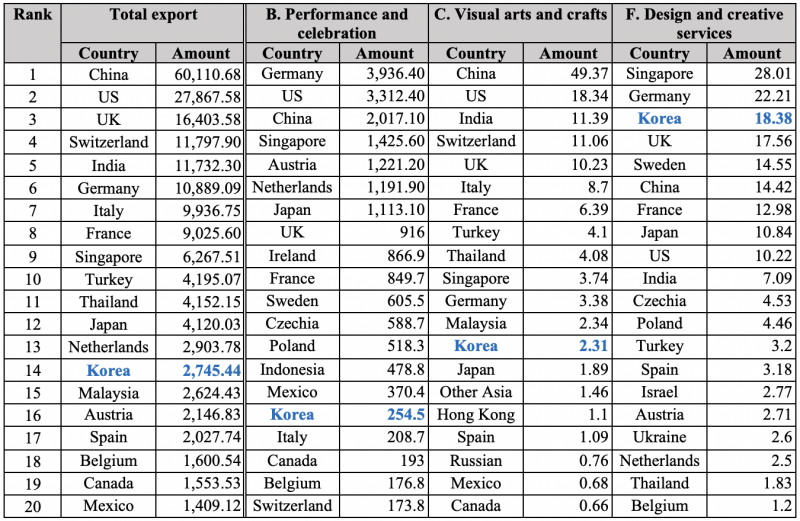

This success gives the impression that Korea is way ahead of other countries when it comes to the export of cultural goods. However, such a perception based on anecdotal evidence requires careful in-depth verification and careful analysis of official statistics. When the total export of global cultural goods was measured by UNESCO using 2013 data, Korea ranked 14th out of 184 countries and regions (see “Total export” in Table 1).

Note: Unit for amount is million USD.

Source: UNESCO (2016, pp. 100-108, pp.140-141, pp. 144-145, pp. 156-157).

UNESCO divided this export data into six core cultural domains: Cultural and natural heritage, performance and celebration, visual arts and crafts, books and press, audiovisual and interactive media, and design and creative services. Among each of these six domains, the share of global exports is different.

In 2013, visual arts and crafts accounted for around 70 percent of the total global export, whereas ‘performance and celebration’ and ‘books and press’ accounted for around 10 percent respectively. Korea is only listed within the top 20 for performance and celebration (16th), visual arts and crafts (13th), and design and creative services (3rd). This is very different from the common perception, considering that Korean popular cultural goods such as K-pop, dramas, and films fall under audiovisual and interactive media. It should be noted that the contribution of this category to the total export of global cultural goods is very marginal compared to the other domains.

It could be argued that this might simply reflect the age of the data, which precedes several notable breakthrough successes such as BTS or Parasite. This is true, but there are still three very important messages that emerge.

First, the categories where Korea is positioned in the top 20 are more related to what I have termed as ‘accumulable’ culture (universal, modern cultural fashions in realms like music and film), not ‘accumulated’ (the cultural heritage of the nation-state aggregated over its history and intrinsic to identity). When favorable conditions are fostered, industries manufacturing accumulable culture can prosper regardless of the strength or inter-cultural appeal of accumulated culture.

Second, given what we know about the transmission of Korean popular culture through modern modes of communication such as the internet and the associated growth of content on new generations of communications devices, it is possible to argue that this factor was missing from data for audiovisual and interactive media trade.

Third, the soft power impact of cultural goods is amplified by advances in these modes of content delivery. In any case, it is necessary to seek and analyse more recent data.

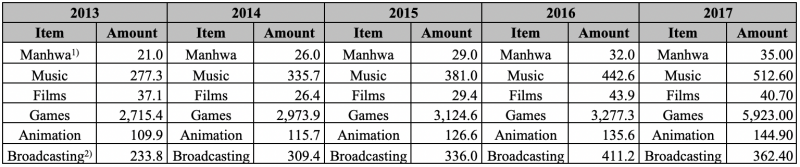

As shown in Table 2, the export of most Korean cultural goods has increased substantially between 2013 and 2020, but in some categories accelerated especially rapidly between 2019 and 2020. This might be partly explained by consumption habits during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Squid Game attracted an ardent following on Netflix in western markets, perhaps capturing the zeitgeist of the times.

Notes: 1) Manhwa is the general Korean term for comics and print cartoons. Here, it includes webtoon which is digital comics; 2) Broadcasting includes drama series as well as other TV programs; Unit for amount is million USD.

Sources: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (2017, p. 71; 2021, p. 68).

Some might argue that this increase in the export of Korea cultural goods helped to enhance Korea’s soft power. However, Table 2 is not sufficient to demonstrate any causality between soft power and the export of cultural goods.

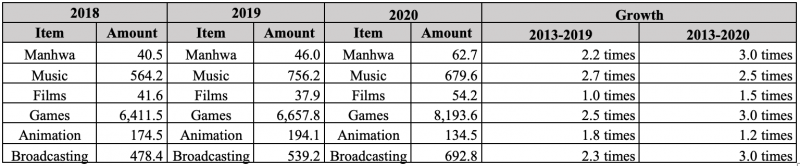

The recent focus on the export growth of cultural goods risks giving an exaggerated impression of its contribution to the economy. The reality is that export of cultural goods pales in comparison to exports of semiconductors, automobiles, ships, and intermediate industrial goods. When games are excluded from cultural exports, they do not appear in the list of top exports (see Table 3); the total value of cultural goods exports is equal to just 1 percent of the value of semiconductor exports.

Note: Unit for amount is million USD.

Sources: e-narajipyo (2022) and Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (2021, p. 76).

Notwithstanding the relatively small size of cultural exports, the disproportionate international media attention they have received — at least from an economic value point of view — attests to something else at work. This might be partially due to the ‘glamour factor’ – the stars of popular culture naturally attract consumer and media interest. People are more interested in their entertainment options than the underlying economic realities.

So, if the direct economic contribution is relatively small, do cultural exports provide other benefits for the producer by enhancing soft power?

First, it could be argued cultural exports enhance Korea’s image and reputation abroad, particularly by synergistically reinforcing its ascent up the industry from one-time maker of medium-priced and medium-quality goods to the current generation of sophisticated and high-quality manufactures produced by marquee Korean brands.

Second, the record suggests cultural exports provide another indirect boost to the economy by driving tourism. Tourism revenues hit USD 20.7 billion in the year before the pandemic, doubling in value over the decade. In the early days of Hallyu, the TV drama series Winter Sonata proved a huge hit in Japan, bringing large numbers of mainly middle-aged female devotees to view the locations where the show was filmed. This can’t have done any harm to often fraught Korea-Japan relations.

Third, the consumers of Korean culture might more broadly acquire interest in, and sympathy for, Korea’s geopolitical and historical challenges and its values. For example, because of BTS many international fans learned about several historical events such as Japan’s occupation of Korea and the Korean War from Korea’s perspective. Given that the bulk of international fans are young and that they are potential future authority figures, the cultural industry could produce some lasting soft power rewards.

Dr Jimmyn Parc is an associate professor in the Department of East Asian Studies at the University of Malaya and a research associate at the Institute of Communication Research, Seoul National University. He has been a visiting lecturer at Sciences Po Paris. His research on Korean cultural exports is supported by the Institute of Communication Research, Seoul National University.

Banner image: K-Pop boy band BTS record online public service video addressing the recent surge in anti-Asian racism in the US with President Joe Biden, Washington, D.C. US - May 31, 2022. Credit: The White House, Flickr.