Obstacles to advancement for women into leadership roles

By Asialink Diplomacy

Multiple obstacles to women’s leadership are evident throughout Southeast Asian countries and Australia. The head of UN Women, Lakshmi Puri puts it simply when she describes the ‘stubborn tradition, culture and religious influences’ in Asia which ‘jostle with, if not fight against this progressive and modern outlook’. On Australia, a senior male corporate leader explains the situation thus: ‘Australia has deeply entrenched and outmoded social attitudes and norms around gender roles at home and work. The concept of ‘mateship’ is too often abused as a proxy for [or to legitimise] the exclusion of women by men.’

From Islam in Malaysia and Indonesia, to Buddhism in Thailand and Myanmar, the Confucian heritage in Singapore and Vietnam, or Christianity in Australia, major religious traditions have depicted women as the maternal anchor of family life. They are also often the guardians of national culture.

The historical legacy of discrimination continues to surface across every country.

For example, the 2015 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics survey in Australia which suggested most men were happier with their wives at home, instead of employed in a workplace.

Across the region, social patterns have become entrenched and reinforce sources of gender discrimination. For instance, the domestic economy in many rural areas is dependent on unpaid female labour to support male employment. This narrows the pool of future leaders as young women are often denied skills training for fear that an investment in them will accrue to another family after marriage. The prevalence of early marriage and high adolescent fertility rates in Lao PDR, the Philippines, Cambodia and Indonesia also act to reinforce household demands on women.

As identified in the World Bank’s 2016 Women, Business and the Law Report, in most countries there are at least some legal barriers to women’s leadership. These can limit women’s full economic participation and restrict their ability to engage in entrepreneurial and employment activities. For example in Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia and Malaysia certain tax provisions directly favour men, and widows do not have equal inheritance rights.

For aspiring female politicians, the usual route to promotion through electoral politics is still dominated by traditional practices which are fundamentally resistant to change. Party gate-keepers often allocate campaign funds and influence nominations, and young women find it difficult to access the male-dominated networks though which this patronage system operates. To work outside this system, aspiring leaders can struggle to juggle household responsibilities and raise the money to campaign.

Female politicians who successfully navigate party bureaucracies still encounter resistance from a sceptical voting public, which can sometimes involve threats of violence and harassment. As with the media treatment of Prime Minister Julia Gillard in Australia, or Dyana Sofya in a recent Malaysian by-election, the campaign of female politicians can become side-tracked with the media focusing on trivial issues like appearance and marital status. Those who do succeed, like Corazon Aquino or Aung San Suu Kyi, are exceptional and held up as icons.

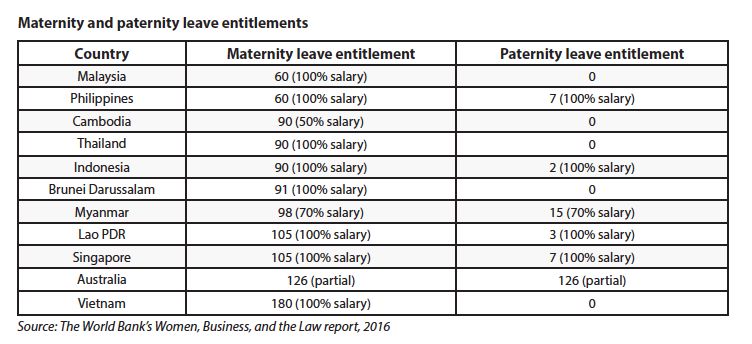

In the corporate sector, thinking has shifted away from the idea of a glass ceiling blocking access for women. Instead, the focus is increasingly on the many small-scale challenges for women which can derail the upward trajectory of promising careers. Whether it is due to a lack of options for maternity leave and child care, or office demands which sit uneasily alongside household responsibilities, workplace pressures disproportionately affect females. This is particularly challenging in some parts of Southeast Asia and Australia, with statistics pointing to persistent gender pay gaps and limited child care options.

Top-down decisions may deliver some cosmetic changes, but they do not guarantee lasting improvement unless there is a supportive infrastructure to nurture an organisational pipeline of young talent.

While there has been more targeted recruitment of women in the corporate sector in recent years, in both Southeast Asia and Australia many early and mid-career women fail to successfully transition into senior management as part of a ‘leaking pipeline’ in talent promotion. In one recent survey, executive teams in Fortune 100 companies in Asia had an average of less than 5% female members.

Policy and implementation vary across the region, but even the most accommodating organisations struggle to overcome the influence of gender stereotyping. Interviews with female thinkers and leaders across the region by the LKY School in a 2014 report pointed to a common challenge of ‘unconscious bias’ operating against women, shaping their treatment in a professional context. Businesswomen are often dismissed as risk averse, and younger entrepreneurs struggle to raise funds for new ventures because there is little custom of women holding financial assets. These biases cross gender lines too, with many surveys showing large numbers of women believe their male colleagues are more suited to leadership than their female counterparts. For all the variations across the region, therefore, a common history of subordinate roles for women will be difficult to reverse in any country.

Image: Corazon Aquino swears in as president of the Philippines at Club Filipino, San Juan February 25, 1986

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons