Hugging Bears - an address by Carrillo Gantner AC

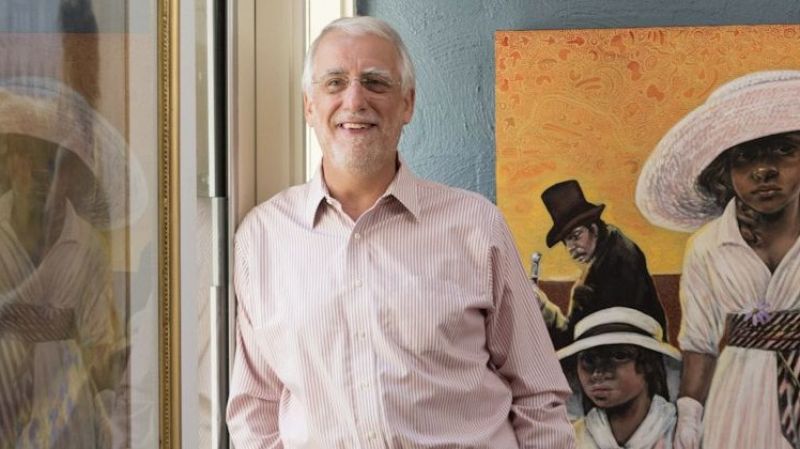

Carrillo Gantner, Patron of Asialink and former Chairman, first visited China in February 1977 and went on to become one of the most influential Australian cultural ambassadors in history. This year he delivered the Annual Address for the Australia-China Institute for Arts and Culture.

Let me start by acknowledging the traditional owners of this unceded land around Parramatta, the Burramatta people, a clan of the Darug, who lived along the upper reaches of the Burramatta River which I learned means the place of eels. I pay my respects to their elders past and present, and to any other First Nation people here today. It is fitting here at an Institute focussed on arts and culture that we acknowledge that we, like all Australians, are the beneficiaries of the rich traditional culture of the first inhabitants and of the vibrant contemporary expressions of this culture in the visual and performing arts.

Can I also please pay my respects and give my thanks to a couple of our own elders. First to Professor Wang LaBao, the distinguished Director of the Australia-China Institute for Arts and Culture. I thank you for inviting me here today. My thanks also to Dr Jocelyn Chey, the founding Director who introduced me to the Institute. Jocelyn is, in fact, an old friend from across the decades and over the seas. As many of you will know, Jocelyn was the first Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy in Beijing after diplomatic relations were established with the People’s Republic of China in 1972 by our wonderful Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.

Now I have already blown it by appearing to take political sides which is entirely undiplomatic, but this is a personal thing - it was truly exciting to be young when Gough was elected after long years of conservative political torpor in Australia. On Gough Whitlam’s first day in office, when only he and the Treasurer Lance Barnard had been sworn in to Cabinet, Gough did two extraordinary things towards which the majority of young Australians had been working for years: he recognised the People’s Republic of China and he withdrew Australian troops from the quagmire of the Vietnam War. Not a bad day’s work.

As the English poet William Wordsworth wrote in another context altogether:

"Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven.”

We talk of establishing diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1972 as though this was the very first time China ever came on to the Australian radar. We usually forget, or perhaps we never learned, that Australia had had diplomatic relations with the GuoMinDang or Nationalist Government of Chiang KaiShek in Nanjing prior to their defeat by the Communists and the declaration of the People’s Republic in 1949. And, of course, the Chinese had been in Australia in considerable numbers since the Gold Rushes of the 1850s. There was some very deep racism against the Chinese in those early colonial years. Today we are unfortunately seeing shadows of that racism again, but that is another lecture for another day.

I would like first to make some introductory comments that give some context to my remarks this afternoon.

The first and perhaps most important thing to note is that my comments are already stale and out of date. I am old hat. I am also not a scholar. I am essentially an artist and an arts administrator with a practical bent. I like to do things and am not so good at thinking about what they mean. Others do this much better than me.

The China I worked in in the mid 1980s has long since gone. China is vast. China is complex. China changes so rapidly it is not possible for a part-time observer like me to keep pace. I used to say that “the more you go, the less you know.” To date myself and give you an idea about how much things have changed, when I went to work at the Australian Embassy in 1985, I carried with me one of the very earliest Apple Macintosh computers. It was the size of a small suitcase and it could only be used it for word processing. Emails were not yet used for daily communication and Google and Facebook, let alone Alibaba and Tencent, did not exist.

My wife Ziyin grew up in the Cultural Revolution and, coming from an artistic and intellectual family, ”The ninth stinking class” as they were called in that wonderfully colourful language of the time, they suffered a great deal. Her grandfather was killed in front of her, her parents were sent to labour camp, schools were closed, and she was sent to live with relations on a naval base. Almost ten years of national chaos, personal tragedy, political isolation and economic disaster; and yet to many of the young Chinese students studying in Australia today, about as distant and foreign as the French Revolution about which Wordsworth was writing in those lines I quoted above.

I first went to China in February 1977, just after “The smashing and renunciation of the Gang of Four”. Again, the colourful language and again I get blank stares from young Chinese. I would have been significantly older than the students in this room when the Great Helmsman himself, Mao ZeDong, died in October 1976 and after him, the rise, or should I say the return, of Deng XiaoPing. Gods in their day, Mao and Deng are now ancient history to the young Chinese we meet today. I may as well be talking of emperors from distant dynasties like Qin ShiHuang or Qianlong.

These young Chinese, many of whom are studying here in Australia, and some of whom remain as permanent migrants, have grown up in a different China to the one I first saw in 1977, a China that today has made an extraordinary shift in two generations towards middle income prosperity. They are highly educated and interested in most of the same things that my children are – salaries, holidays, music, food and fashion. They come from a culture that places education as central to advancement in life. A high percentage of them are both smart and very well educated. Even if they don’t like aspects of their Motherland, these young Chinese feel attachment towards it, they are proud of China’s rise in world affairs and they feel a proper patriotism, as they should. That doesn’t make them stooges for China, let alone spies working against Australia as Clive Hamilton in his book Silent Invasion would like to suggest.

I am rather proud that I too was criticised by Mr Hamilton, not quite a security risk but clearly a ‘Panda Hugger’. Why? Because I promoted the tour of the National Ballet of China with their production of The Red Detachment of Women which we brought into the first Triennial of Asian Performing Arts, Asia TOPA as it is called, in 2017. This was the ballet version of one of the eight Model Operas from the Cultural Revolution. In the late 1960s, these eight propaganda-heavy stories were virtually the only ones allowed to be seen and heard in any form of public entertainment – Chinese opera, dance, drama, puppetry and so on – and people grew utterly bored with them. Today they are historical curiosities, devoid of any sting of propaganda power. Who cares that they were once designed to educate the masses, and especially “the Workers Peasants and Soldiers”? I had only seen the Model Operas on film or heard the music in recordings so, for me, the chance to experience one live, performed by one of the world’s truly great ballet companies, was something special and worth pursuing. For my wife, these Model Opera were her childhood Harry Potter, except with a very sour taste because the children at their Hogwarts really did kill some of their teachers and the Red Guards of Lord Valdemort really did bring chaos and death to so many.

Even before I first went there in 1977, I was interested in the performing arts of China. There was something very powerful happening in a country that had initiated ten years of national convulsion on the back of a review of Wu Han’s play “Hai Rui Dismissed From Office”. I had tried through the Chinese Embassy in Canberra to get permission to take an Australian theatre group into the country and to arrange for myself to work with a Chinese troupe in Wuhan, unsuccessfully in both instances. Then in Beijing on that first trip with a group from the Committee for Australia China Relations (a group founded in 1972 by Stephen FitzGerald and Myra Roper to lobby for formal recognition of the PRC), I was summoned down to the foyer of the old Beijing Hotel to face some unidentified officials. I thought I must have offended some local custom and was going to be expelled. Instead I was invited to return to China with an Australian theatre group. It took a year to organise and select the group but in 1978 I led the first professional theatre tour from the West to China since the end of the Cultural Revolution. We saw many shows, visited many performing arts companies, spoken theatre and traditional opera schools, acrobatic troupes, music conservatories and symphony orchestras. We saw an extraordinary wealth of national cultural resources, all trying to rebuild their infrastructure, repertoire and craft, all desperate to make linkages with overseas countries and artists from whom they had been cut off for a generation.

There was a real desire from others at home, so I took another group of Australian theatre artists to China in 1979. This same year the Fujian Puppet Company, a small troupe of brilliant glove puppet artists, was invited by Australian puppeteer Richard Bradshaw who had been in our first group to China the previous year, to participate in a puppet conference in Hobart. I asked if we could present them at the Playbox Theatre in Melbourne where I was Artistic Director. We did so, and with such success that at the last minute we were asked by the Chinese Embassy to extend the tour to Sydney and Canberra. On the strength of this, the Embassy asked me to organise a national tour by a major acrobatic company the following year. The Nanjing Acrobatic Troupe was chosen because Victoria and Jiangsu had recently signed the first Sister State Agreement between Australia and China. And because this was a touring company of 50 artists and production personnel playing a week in every state capital, I invited my friend Clifford Hocking, a commercial theatre entrepreneur, to work with us. We toured the Company under the banner of Playking Productions, 50% Playbox Theatre and 50% Clifford Hocking. We figured ‘Playking’ sounded somewhat like Peking, Nanking and Chongking, and was far more suitable than Hockbox.

Arising from the success of this tour, in 1983 I invited back seven senior artists of the Nanjing Company to teach young Australians working with the recently formed Flying Fruit Fly Circus and with Circus Oz, as well as some independent theatre artists, in what became known as the Nanjing Acrobatic Training Program. This ran in Albury/Wodonga for three months over the summer of 1983/84. The program was repeated the following year. It led directly to the formation of the National Institute of Circus Arts in Melbourne and the transformation of the Australian circus, acrobatic and physical theatre. I am very proud of this initiative. And again I am grateful to Dr Jocelyn Chey. She was by this time, the founding Director of the Australia China Council, the first of the bilateral Councils under the Department of Foreign Affairs, and, unlike most people I tried to convince about the potential of this work in Australian and Chinese official cultural circles, she believed in the program and persuaded the ACC to invest the very first funding of $5,000 in the project. Thank you again, Jocelyn.

We went on to tour the Jiangsu Peking Opera Company around Australia in 1983 and to bring the Hunan (rod) Puppet Company to perform in Melbourne. Some years later I also brought back teachers from the Jiangsu Company to work with acting and directing students at the Victorian College of the Arts, not because I wanted to produce Australian Peking Opera performers, but because I wanted to introduce a different and non-naturalistic theatre vocabulary to some of our young artists in the hope of influencing their future work. Within the Playbox Theatre I was also trying to exert an Asian influence in our programming, selecting plays by Australian writers on Chinese and Japanese themes, commissioning Asian Australian writers, travelling to China regularly and receiving delegations from these countries to form connections and networks for our Company. I used to say that my definition of happiness was ‘To act in one play a year, direct one play a year, and go to China once a year’. Most years I was very happy!

In all of this work I had strong connections with the Cultural Counsellors at our Embassy in Beijing. In 1984, Sam Gerovich who was then in the role, encouraged me to apply for the position which he was vacating in April 1985. I did so and, very bravely I think, Foreign Affairs selected me, a professional theatre artist, as the fourth Australian Cultural Counsellor to our Embassy in China. What did I offer for the job? I had excellent contacts in the Ministry of Culture and some provincial cultural agencies; I had travelled around many parts of China; I had wide knowledge across the Australian performing arts sector; I was a self-starter and a very competent manager; I knew that the essential things for travel in any foreign country were curiosity and courtesy; and I could say “Ni hao”. I got my security clearance, arranged my personal affairs and worked on my succession at Playbox Theatre while the Department sent me to the language school at Melbourne’s Point Cook for one term for a crash course in kindergarten Chinese followed by a month at language school in Taipei where the food and the Palace Museum were wonderful but my pathetic language skills went backwards, confused by the long form characters and the Wade Giles instead of the Pinyin system of romanisation. I arrived in Beijing in April 1985.

The Australian Embassy in those days was a much smaller place with a smaller staff than today. I found myself with a range of responsibilities way beyond the known fields of the arts and cultural exchange. In addition to these, I was responsible for the work of the Australia China Council; for sport (an important part of Australian culture); for science and technology; for conservation and the environment; for agriculture (where I used to say that the only logic was the spelling); for law, accountancy and other professional exchanges; for the 25 or so Australian students then studying in China (but not those Chinese students who at that time were just beginning to go to Australia, mostly on government sponsored scholarships); and for anything else that came to the Embassy that was not politics, aid, trade or defence.

Once again I crossed paths with Dr Chey who was now Australia’s Senior Trade Commissioner at the Embassy and always a great source of counsel for me. I recall that early on we had a delightful demarcation dispute about whether wine was trade or culture? We settled this very amicably by concluding that when you sold it, that was clearly trade, but when you drank it, that was culture!

I was blessed in my job by having a really wonderful Ambassador for most of my term at the Embassy, Professor Ross Garnaut. The Ambassador is the Captain of the ship. Ross had been Prime Minister Bob Hawke’s Senior Economic Advisor before his appointment as Ambassador to China. He had devised the iron ore strategy for China that in subsequent decades has benefitted Australia with tens of billions of dollars in trade. He had a brilliant mind and was very well connected to the Chinese leadership. We also had a very capable Minister, or 2IC, David Ambrose at the Embassy, a former classics lecturer turned diplomat from the University of Western Australia, a thoughtful analyst, charming and speaking good Mandarin. I was fortunate that Ross was not a career diplomat obsessed with protocol and rules. He told me just to get results and to call on him if I needed his help with political muscle back in Australia. I did call on this from time to time because, while the Chinese bureaucracy was vast and always opaque so you very seldom knew where the obstacle might be, the Australian bureaucracy was smaller and more transparent. You knew who was blocking the desired outcome and Ross knew the people who could clear the drain.

When Ross was grappling with an issue, he sometimes called the six or seven senior people together at the Embassy and we would each try to address the subject from our own vantage point and understanding – political, strategic, trade, aid, immigration and culture. Ross would then take our various contributions and, within a day or two, weave them into rigorous and analytical papers which would be sent off to the PM and other senior Australian government ministers and officials. I had nothing but total admiration then for the clarity of his thinking and I still feel the same way as Professor Garnaut continues to make a huge contribution to Australia as our foremost economist on Asia, on the study of the impact of climate change, and in many other areas of government and business.

When I look back on my time in China, there are many highlights that come to mind across my many portfolios, but the core was always my work in the arts and cultural exchange. Sometimes I used to joke that I was the first cultured Cultural Counsellor because I came from the theatre whereas my three predecessors, as talented and successful as they were, were all career diplomats. I loved going to shows and often they taught me about issues that were current in the wider society. I kept a diary of 187 performances I saw in just over two and a half years of every kind of Chinese performing art and by international touring companies. I oversaw the negotiations to determine the contents of the annual two way implementing program under the Cultural Agreement between our countries. I negotiated a tour to China by the Australian Ballet. I introduced Chinese artists and companies to Australian counterparts, and vice versa. I could do this directly because I knew the Australian arts scene so well. I did not have to send a note to the Cultural Relations Branch at DFAT and hope that they might have an idea about with whom the artist or company might link. I shepherded Australian artists and cultural delegations that did come to China. And I recommended some brilliant Chinese artists directly to the right entity: superb tenors I was hearing to the Australian Opera, for instance, or outstanding conductors to the ABC who managed Australia’s major symphony orchestras at that time. I have to say that they almost always totally ignored my recommendations because senior Australian arts managers were appallingly Eurocentric. Sadly this is still often the case though it’s improving. China was simply not yet in their imaginative sphere and even the greatest Chinese artists were entirely off their radar.

I tried to make sense of what I was seeing and hearing across the cultural sector and write reports for DFAT that attempted to analyse the significance of this not only in the cultural sphere but also political. It sometimes surprised my colleagues in the political section of the Embassy that I was able to detect trends and the threads of some new political winds before they did. This was simply because, in China, culture is very close to ideology and the cold winds of change frequently struck the artists’ cheeks before those of others. In every Asian country I know, culture is at the very centre of life through a broad understanding of one’s language, history, education, art, food and even politics, whereas in Australia many people still seem to think it is what you do on Saturday night.

I had many adventures across my portfolios, but I only have time to share a few with you here this evening. Let me start with my directing an Australian play for the Shanghai People’s Art Theatre in 1986.

After a long meeting to discuss my experience and ideas, I received the invitation from the grand old man of 20th Century modern Chinese spoken drama, or ‘hua ju’, Huang ZuoLin. Having been given permission buy Canberra to do this, I was introduced to the Artistic Director of the Shanghai company, the noted and often controversial playwright Sha YeXin. The Chinese Ministry of Culture reported my invitation to the Department of Foreign Affairs who oversaw all foreign diplomatic activity in China. They promptly disallowed my invitation on the grounds that a foreign diplomat could not be a professional play director with a Chinese theatre company. We solved this conundrum with an elegant Chinese and face-saving solution: during the entire rehearsal period in Shanghai and until I returned to my desk at the Embassy in Beijing, I handed in my diplomatic passport with its status and accompanying privileges, and I simply used my ordinary Australian passport like an ordinary visiting artist.

What play would we do? I had four translated and sent to the Company for them to choose. I thought that they would choose the Australian classic, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll by Ray Lawler, a work that is thought to mark the beginning of the new era of Australian playwriting beginning in the mid 1950s. I proposed to set it in Shanghai with the central characters Roo and Barney played as labourers in the pineapple fields of Fujian rather than the sugar cane fields in Queensland. The Company surprised me entirely by their selection of Jack Hibberd’s A Stretch of the Imagination. It is a superb piece of idiomatic and colourful writing, but it’s a one man play. Sha YeXin told me that the Company employed something like 150 full time actors so they always chose large cast plays and had never before done a one man show. This was something new for China.

They cast a terrific character actor from the Company, Wei ZongWan, and I had two translations made by Professor Hu WenZhong from the Beijing Foreign Studies University. Professor Hu had done an MA in Australian literature under Professor Leonie Kramer at Sydney University so he understood our Aussie idiom. He was also known all around China because of the popularity of his English language teaching program Follow Me on national television.

One translation was utterly literal and the other tried to find Chinese equivalent expressions for the playwright’s exotic and sometimes blue (or ‘yellow’ as the Chinese would say) turn of phrase. I used the first translation as a reference to help the actor understand the exact meaning that the writer sought to convey, and I used the second for the production itself so that audiences could feel more attuned to the flavour of the work.

We rehearsed in a studio at the Shanghai Drama Academy. During the three hour lunch break, I rode my bike to the Australian Consulate General where unofficially I acted in the role because we happened to be between incumbents at the time. In the rehearsal room, I had a full-time interpreter by my side who could explain the complexities of language and meaning, but we quickly found that the actor could best understand my direction around the character’s physical expression when I acted it out myself on the floor. About ten days before the opening, all the senior leaders in the Company came into the rehearsal room to watch a run through. I was then put though a rigorous but respectful session of ‘criticism and self-criticism’ which was tough to absorb yet tremendously valuable not only in improving the production but also in my learning something about humility.

Then, just before we were to open at the Lyceum Theatre across from the Jin Jiang Hotel in central Shanghai, the City’s Cultural Bureau declared the production “Nei Bu”. Essentially this means that the work was thought to be offensive or otherwise problematic and that therefore only members of the Communist Party could see the show as they were thought to possess sufficiently strong moral fibre to be able to resist the play’s corrupting influence. The general public could not buy tickets. The Minister in our Embassy, David Ambrose, flew down to Shanghai. He and I took the senior officials of the Cultural Bureau to a long lunch and box office disaster was averted. The offending moments in the production seemed to be the actor’s simulated but utterly convincing urination into a barrel, and an extravagant line in the script which was followed by the words, “Homer said that”. The translator had used the common transliteration for the classical Greek writer’s name as “He Ma” but in other tones this meant Hippopotamus which, unbeknown to me, was street slang for the ageing Mao ZeDong. Inadvertently we were sending up the Chairman. David was so charming at lunch that all restrictions were lifted and the production allowed to proceed as it was. Both moments drew gasps and embarrassed giggles from the audience every night.

I wanted to write a book about the whole experience as Arthur Millar had just done around a production of his Death of a Salesman in Beijing several months before, but I lacked his fame and couldn’t find an Australian publisher. The first chapter I had written as a teaser was subsequently published by the Australian literary magazine Meanjin out of Melbourne University. It’s a pity because I loved Shanghai, I loved the daily creative stimulation of cross-cultural rehearsals, and I look back on this experience as one of the very happiest and most satisfying couple of month in my life.

Another great experience was twice to travel around China with Gough Whitlam himself when he was the Chairman of the Australia China Council. Everywhere we were treated like kings because the Chinese remembered that Gough had gone to China even before Henry Kissinger was sent as Nixon’s emissary, and had brought about diplomatic recognition well before the Americans. I took the notes for his meetings with Deng XiaoPing who chain smoked and spat into a spittoon between their chairs while Gough paused his question, and with Premier Li Peng, a dry technocrat who was no match for Gough’s supple mind. We travelled in motorcades and were accommodated in stage guest houses or the Presidential suites of five star hotels. In Shanghai we were accommodated in the same suites with huge black marbled bathrooms that President Nixon had occupied on his visit to China in 1972. They gutted a cabin and built a specially long bed for Gough when we travelled down the Yangtze on the ferry The East is Red No 52.

Gough had a brilliant capacity to capnap in the car between meetings. He would say, “Wake me five minutes before we get there” and promptly nod off. I would wake him and read the briefing notes for the next call. “We ae visiting the Chengdu Light Industry Factory No 27, a joint venture between the Sichuan Department of Light Industry and the Australian Company XYZ. The General Manager, Mr Wang Li, will be receiving us”. Then our Red Flag limousine would sweep into the factory driveway and Gough’s towering frame would step out of the car, hand extended to the receiving hosts. “Mr Wang, I have heard so much about your distinguished career and have been looking forward with enormous anticipation to meeting you and visiting the great Chengdu Light Industry Factory No 27, a glorious joint venture between our great Australian company XYZ and the famous Sichuan Department of Light Industry that has contributed so much to the well-being of the people of New China”. Mr Wang reeled back and we were led inside for an inspection of the manufacturing processes in the spotless factory. At some point as the tour progressed, Gough leaned towards me and whispered in a conspiratorial voice, “Comrade, what am I looking at?”

1988 marked the celebration of Australia’s Bicentennial. Two years previously, Prime Minister Hawke had visited Beijing and met with the then Chinese Premier Zhao ZiYang. Among other things, they agreed that, as China’s birthday present, they would loan two giant pandas to Australia for the year. Because this fell within my responsibilities for Conservation and the Environment, I was given carriage for negotiating the deal with the Ministry of Forestry and Fisheries. For almost two years I met the Chinese officials once a month for what I used to call “three tea pot meetings” and which today would be called “full and frank discussions”. We covered an immense amount of detail in matters such as transport, security, feeding, facilities at the Australian zoos, quarantine, living arrangements for their keepers and , of course, fees. The Chinese are masterful negotiators – they only fear dealing with the Japanese who know their wiles - but I learned quickly, resisting what I regarded as outrageous “rent a panda” terms and regularly retreating to another cup of tea, talk of ‘friendship between our two great leaders’ and /or ‘two great peoples’, and the obvious line that it was not appropriate to be offered a birthday present and then be presented with the bill. When we found we had no agreement about certain clauses, we would have yet another cup of tea and agree to meet again next month. I recall at one meeting having some success around quarantine issues. When I returned next month, a different official, I will call him Mr Min, arrived to greet me in the meeting room. He apologised that my regular counterpart, Mr Wang was had to travel somewhere, and asked what we had achieved at the last meeting. I pulled out my papers and read off the list of issues upon which Mr Wang and I had reached firm agreement. Mr Min adopted a solemn face and said, “Oh dear, unfortunately Mr Wang was not authorised to deal with these quarantine issues. We will have to look at those again….”

And so it went, month by month, until the Melbourne and Sydney zoos which had invested over a million dollars each to build new enclosures, grow the appropriate bamboos and import panda merchandise for their shops, became panicked and both the Ambassador and I received constant Australian government instructions to sign up. I refused to accept what I thought were outrageous terms. I tried to reassure the Australian parties that there was absolutely no chance that the pandas would not arrive in Australia on schedule because this had been agreed by the two leaders and widely publicised. There was a serious issue of face involved. I predicted that negotiations would go to the door of the airplane that would be sent to collect the pandas. Then my term finished and I went home. My successor as Cultural Counsellor, Dr Nick Jose, subsequently told me that In fact they went past that moment because, when the Qantas jumbo pulled up to load the pandas, the Chinese determined that it was inappropriate for their national animal to be pictured waving goodbye beside the Qantas logo. At the very last moment they switched the loading to an Air China plane, the photographers took their pictures, and the pandas flew with their own national carrier to Tokyo where they were reloaded onto the Qantas aircraft.

In 1986 I accompanied our Minister for Science, the brilliant Barry Jones, to China’s rocket launching base at Xichang in Sichuan Province. Australia was looking at the potential for China to launch its first generation of communication satellites on their Long March rockets. We were only the second foreign delegation allowed onto this military base and security was very high. We did not see an actual launch but were taken up the launch tower and shown a film of a previous launch in the vast control centre with rows and rows of computer banks. I recall that the Minister spotted one man intently working at the screen of a distant computer, so, trailing our delegation and minders, the Minister made a beeline for him. To the Minister’s delight, it turned out the fellow was playing Pac Man on a Taiwanese monitor.

While in Xichang, we were taken out to a Buddhist temple above a beautiful mountain lake. Suddenly speedboats came roaring around the corner pulling a group of waterskiers. I turned to our military host to ask what they were doing in this remote location? “They are training for the Olympics,” he said, to which I replied with the obvious retort that waterskiing was not an Olympic sport. “Ahhh,” he said thoughtfully, “But when it is, China will be ready.”

Traveling back to Chengdu on an overnight train, I was sitting having a drink with our minders from the State Science and Technology Commission for Defence. One of them asked me how I was enjoying my time as a diplomat. I said that I really loved being in China, that the job was constantly different and challenging, but that, after a life in the theatre, the only thing I was struggling to come to terms with was being treated as a spy – having my phones tapped, my movements watched, occasionally being conscious of being followed in the street, the cook making notes of who came to dinner which he had to submit to the Diplomatic Service Bureau. Initially the minders said, “Oh no, that couldn’t happen here,” but as I gave examples they laughed and started telling me of their own experiences when posted as the Science Counsellor in various Chinese Embassies abroad. One small story from that night stays with me: They told me that one day the head chef cut his hand very badly with a knife while working in the kitchen in the lower reaches of the Chinese Embassy in Washington. The ambulance was there before they made the call.

I used to say flippantly that diplomacy was a child’s game played by adults. We were not allowed to drive to the coastal resort at Beidaihe in Hebei Province where the Chinese leadership held their summer retreat and, more to the point, where the Australian Embassy had a beach house we could use occasionally for weekend recreation. We had to take the train. In return, Chinese diplomats in Canberra were not allowed to drive to Bateman’s Bay on the NSW south coast but the Chinese policy of ‘equality and mutual benefit’ could not be applied as there is no train to Bateman’s Bay.

Cultural diplomacy is, in fact, a serious business and yet Australia seriously underestimates its potency. China does not. China is investing big efforts and big money in so-called soft power initiatives to win friends and influence people. After arguing for over 40 years that Australia needs a dedicated agency to promote Australia’s image abroad – and I mean that in a wide sense to include academic exchange and other broadly cultural programs – we still have a hopelessly fragmented approach with very modest pockets of money with the Australia Council, with DFAT, with the various bilateral Councils under DFAT, with state and local government arts agencies, and with other peripheral entities. We have no national strategy even to coordinate these, let alone an organisation devoted to the job such as the Japan Foundation, The Korea Foundation, the British Council, Germany’s Goethe Institute or the Alliance Francais. It is a nightmare for an arts organisation seeking funding to tour to Asia. You get a little bit here, a knockback there.

Worse, Australia has no career structure for arts managers who want to work in the field of international cultural exchange. When he was Australian Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer, removed the Cultural Counsellors from our major embassies in Asia, arguing it would save money. In line with the Howard Government’s wider policies, we kept these positions in Washington and London. Their responsibilities were given to the Public Affairs Counsellors whose main work is seeking favourable local media for Australia and especially for visiting Australian Government ministers. Our major Embassies in Asia now service the cultural area with locally engaged staff who do not get the living allowances of A based staff. Most of them are therefore from the host country though some are Australian. They are keen and wonderful people, but they lack seniority and often don’t know either the cultural scene in Australia or the host country very well.

Many years ago, our Government ceased the practice of having a mutually agreed annual implementing program under the Australia-China Cultural Agreement. Again, it was to save money. Now it’s a free for all which has many virtues and encourages opportunity and diversity from self-starters and those with organisational muscle. And yes, it has reduced DFAT’s budget in this area but it has cost every touring company, and therefore Australia, much more because now every negotiation starts with no agreed ground rules about who pays for what.

The great Chinese American cellist Yo Yo Ma said that “Culture helps us imagine a better future”. We desperately need this now when America and China are at loggerheads, when the US President is a corrupt and dismal narcissist and the Chinese ‘Chairman of Everything’ is increasingly autocratic and imperial. Politicians come and go but China’s rise is inexorable and we should be welcoming the opportunities this presents while protecting our own interests which can no longer always be synonymous with America’s interests. We tend to follow the US as a rather timid sycophant when what Australia desperately needs is a more independent, informed, nuanced and sophisticated foreign policy.

In this mix, artists make great ambassadors because they speak the language of the heart, their focus is not transactional and intent on personal or corporate profit, their currency is our common shared humanity. They open doors to mutual understanding that helps us all to deal with the inevitable bumps along the bilateral road. An education system that delivered young Australians with real knowledge of the language, history and culture of China – and, I might add, of Japan, Indonesia, Korea and our other Asian neighbours - would stand us in great stead and repay any investment made to get there many, many times over.

The first time I visited this university, I commented on the large number of Asian students on the campus. My initial impression was that they were overseas students but this is not so. They are largely Australian students who happen to be of Chinese and Indian heritage. They have settled with their families in this region of Western Sydney. They are not just “new Australians”, they are the new Australia. They place a high value on education as the path to advancement and I imagine that their parents have made real sacrifices to help their children get established. I find it very moving that they can love pandas, or perhaps for some it’s Bengal tigers, and they can love koalas at the same time. It’s not a contradiction.

I am planning to come back in 100 or 150 years for a peek at the lives of the great-great-grandchildren of these students. I would bet that that Australia will be populated by a very beautiful Eurasian and honey coloured people. Australia will sit loosely within the Chinese orbit of influence but curiously it will not feel all that different to the American orbit in which we now meekly circle. We will doff our hats to Beijing as we do today to Washington and as we did for the first 150 years of our European history to London. Having done so, we will get on with our lives and go about our business as usual, though now much more closely integrated with our regional neighbours and not least Indonesia. We will enjoy a rich culture that still draws its primary sources from Europe, from English language classics such as Chaucer, Shakespeare and the King James Bible, but now enriched with other colours and textures from Chinese and Indian cultures and classics, Peony Pavilion and Dream of the Red Mansion the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Australian politicians like to boast that we are the most successful multi-cultural society on earth. I am not sure that some current behaviours warrant such self-congratulation. If, however, we do get to the place I am envisaging, we will truly be the envy of the world.

Thank you.

This speech was delivered on April 9 as the 2019 Australia-China Institute for Arts and Culture Annual Address.

Carrillo Gantner studied at University of Melbourne, Stanford University, and Harvard University before taking up his career as a professional actor. He was the Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy in Beijing from 1985 to 1987, and served as Chairman of Asialink Centre at University of Melbourne from 1992 to 2005. From 2005 to 2009, he was President of the Myer Foundation and has been the Chairman of Sydney Myer Fund since 2004. From 2011 to 2013, he was an Advisory Board member for the Centre for China in the World at Australian National University. He was the founder and remains the godfather of the new Asia Pacific Triennial of Performing Arts (‘Asia TOPA’) in Melbourne.

In 2006, Carrillo was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Letters by the University of New South Wales for his services to the arts and the community. In 2008, he was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. In 2014, the Ministry of Culture of the People’s Republic of China awarded him their highest honour for foreigners — “The Cultural Exchange Contribution Award” — for his outstanding contributions to China’s cultural exchanges with the world. Carrillo has written for various journals and other publications, and for decades he has been working to enhance Australia’s reputation as a constructive partner in the Asia Pacific. In April 2017, he was appointed Adjunct Professor of the Australia-China Institute for Arts and Culture, Western Sydney University, and in January 2019, he was appointed to a Companion in the Order of Australia (AC).

More Information

Carrillo Gantner AC