Bracing for the Next Pandemic

By Donald Greenlees, Senior Adviser, Asialink

Pandemic management has been a contest of priorities between the health of citizens, the strength of economies and the security of political systems. Faced with the complex trade-offs, governments have not always been either willing or able to place containment of the virus first.

The quality of pandemic control appears to owe less to regime type – examples of strong and weak policy responses are found among both democracies and autocracies – than to the wit of individual leaders, the strength of economies and national institutions, cultural and social values, and the modernity of health systems.

The reverberations are certain to be felt in a multitude of unpredictable ways for a long time to come, affecting the patterns of domestic and international politics. The ‘virus effect’ on public affairs will almost certainly outlast the pandemic.

Many tests still await Asia. Among the most important will be what the countries of the region do to absorb the lessons from COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, to bolster their defences and response capabilities once the current threat passes. The experience of this pandemic reveals enormous weaknesses in the international system of monitoring and control and of individual state preparations for worst cases.

A woman buys a cloth mask to protect herself against COVID-19, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia - 2020. Image credit: Muhd Imran Ismail, Shutterstock.

What countries do to address the failure will be fundamentally a question of political will that starts at the top. In time, the coronavirus will be halted. But pandemics are rare enough events that governments and communities are quick to move on. They should not this time.

What happens in Asia in response to COVID-19 in particular should matter to everyone because of the region’s historic role in the origins and transmission of past pandemics and epidemics. The region must prepare for the inevitability of a recurrence.

For decades, infectious diseases experts have been warning about the risks of influenza pandemic. Scenario planning by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in the early 2000s found that a serious influenza pandemic would probably kill between 2 million and 8 million people globally. Doctors treating COVID-19 have found it shares many similarities and differences with influenza viruses.

The experts noted back then that “considerably more attention has been focused on protecting the public from terrorist attacks than from the far more likely and pervasive threat of pandemic influenza”.

Passenger not wearing a face mask is refused permission to board tram by driver - 1918.

Passenger not wearing a face mask is refused permission to board tram by driver - 1918.

The message was that all countries needed to do more to improve surveillance, early and rapid reporting of disease outbreaks, occupational safety for workers in close contact with live animals, related measures to limit the risk of interspecies viral transmission, collaboration on vaccine research and vaccine availability, virus testing capabilities, and the resilience of health systems.

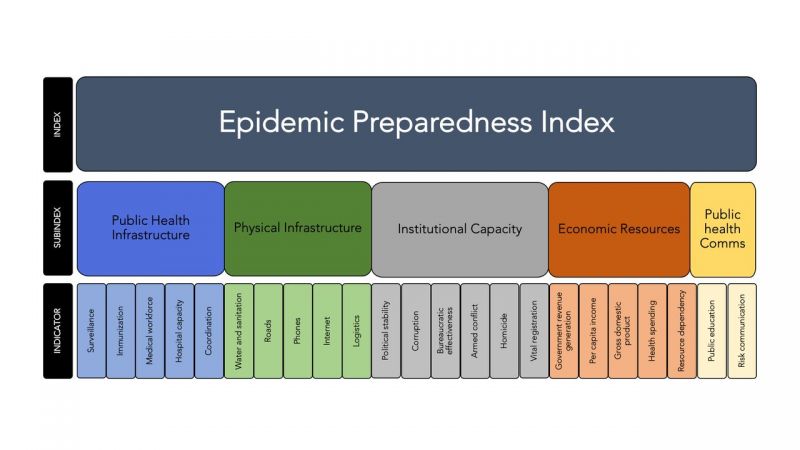

Recent experience confirms national and regional preparedness planning to anticipate economic and social dislocation needs to be added to that list. Studies of epidemic preparedness show countries in Southeast Asia to be among the “least able to detect and respond to epidemics and pandemics” and to be at “high risk for emergence of pathogens with pandemic potential”.

Asia faces significant challenges in large part because of great variance in the levels of development, economic and political incentives to stick with existing food industry practices, and the high costs to national budgets of items that have periodic payoffs and for which success can only be measured by the absence of catastrophic failure.

The ASEAN and East Asia summitry this year, and other international fora like the G20 in Riyadh and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in Kuala Lumpur, face the urgent task of cooperating on solutions to the current global health and economic crises.

But governments also should be starting to think ahead to how they improve coordination on measures to minimise future pandemic threats and manage outbreaks when they occur.

They will have to do a vastly better job than they have in the past. For many years, the region has debated and drawn up plans to contain these threats. One wonders whether individual governments paid much heed.

Tongan AusAID employee Ana Baker walks through Viola Hospital, Nuku'alofa, Tonga - June 10, 2013. Image credit: Connor Ashleigh/DFAT, Flickr.

Clearly, part of the solution has to be more equitable burden-sharing. At a time when many governments in the rich world question the value of the aid dollar, COVID-19 is a reminder that aid can act as an insurance policy.

Rich countries can and should to do more to share knowledge and resources to help Asian countries achieve better disease control outcomes. The Australian government recognised this when it launched the $300 million, five-year health security initiative for the Indo-Pacific in October 2017 with the purpose of building the “region's resilience to health security challenges”.

At the time, the government recognised a range of health security threats, including “growing antimicrobial drug resistance” in relation to diseases like tuberculosis and malaria. The main focus then was on aiding the Pacific and Timor L’este.

The job of leading Australian diplomacy on this big agenda falls to Dr Stephanie Williams, who was appointed ambassador for regional health security on 3 March. Williams is a good choice – an expert in tropical medicine and epidemiology.

It is a good start. But the government must ensure its efforts are properly resourced and that a high priority is placed on collaboration with Asia because of the region’s vulnerability to the emergence and rapid spread of disease in an era of great global mobility.

Even as Australia wages its own fight against COVID-19, efforts to support close Asian neighbors, none more so than Indonesia, will benefit our own health security and other vital strategic and economic interests as we seek to rebound from this crisis.

The record of pandemics also points to the special importance of deepening international cooperation with China, especially on the risk of influenza pandemic.

Soldiers of the US 39th Regiment wear cloth face masks as they march through Seattle, United States - December, 1918. Image credit: Everett Historical, Shutterstock.

There were three influenza pandemics based on novel virus strains in the 20th century – 1918-1920, 1957-1958 and 1968-1970 – and reliable research now points to all of them having Chinese origins. The infamous Spanish influenza of a century ago is misnamed – research in recent years suggests that it had its origins in China and was spread by Chinese laborers who were used to do earthworks behind allied lines in Europe.

Indeed, historians of medicine claim “detailed investigation” shows that out of the 12 pandemics in the 400 years to the turn of the century, 11 of them started in China.

The record this century shows one pandemic – the 2009-2010 swine flu – originating in Mexico and the current COVID-19 outbreak starting in the Chinese city of Wuhan. The 2002-2003 SARS-CoV, which first infected people in Guangdong Province of southern China, was classed an epidemic not a pandemic.

Pedestrians in front of the Forbidden City, Beijing, China - January 25, 2020. Image credit: Javier Badosa, Shutterstock.

A range of factors have contributed to a propensity for pandemics to emerge in Asia and Africa, according to infectious diseases experts. In 2018, a group of seven Chinese scientists, worried about the risks of an influenza pandemic, called on Beijing to “further strengthen its pandemic preparedness and response to contribute to global health”.

Political leadership from Beijing will be vital to, first, rectify internal weaknesses in surveillance, reporting and prevention and to, second, establish a comprehensive regional approach that helps overcome institutional weakness in numerous countries on its borders.

The community of infectious disease experts have a long list of actions they argue governments should take to mitigate the risk of influenza pandemics. The centenary of the outbreak of the Spanish flu in 2018 produced a flurry of such reports. Implementing many of them would test the capacity of several Asian countries.

Epidemic Preparedness Index (EPI) design from 'Assessing global preparedness for the next pandemic: development and application of an Epidemic Preparedness Index', BMJ Global Health journal - January 29, 2019.

One of the most important is sharing “accurate timely information” with the experts and the public, according to the WHO’s latest guidance for pandemic influenza risk management. That could prove vital for the future.

As bad as COVID-19 is, there are viruses with pandemic potential that are even worse – the H7N9 virus which has sporadically infected people in China has had a 39 percent case fatality rate.

The acceleration of Beijing’s efforts to contain COVID-19 following its failure in disclosure when the virus first emerged in December is to be welcomed. But the lesson is clear – early, transparent action and international collaboration are imperative.

The crucial test for all governments is whether the mistakes they made in failing to prepare and react swiftly enough to COVID-19 lead to better systems of prevention and early warning and control.

And that will only come with vastly greater and permanent regional and global collaboration. It will be essential to combating the current pandemic and the inevitable recurrence of virus outbreaks with pandemic potential.

As we weigh the costs to lives and livelihoods of COVID-19, it would be an unthinkable legacy if we failed to absorb that lesson.