Time for a Cross-Party Consensus on Oil and Gas in Dili?

By Michael Leach, Professor, Politics and International Relations – Swinburne University of Technology

Timor-Leste politics finishes a difficult year is an interesting place. The year started badly for the Taur Matan Ruak-led government when its 2020 budget was defeated by its own alliance partner, Xanana Gusmão’s political party, the National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction (CNRT). But Ruak ends the year still in government because the opposition Fretilin stepped in to give his government support in parliament.

This parliamentary “understanding” resulted in a remodelled government. CNRT has gone into opposition after the breakdown of the alliance that won the parliamentary election in 2018. In its place is a government comprising Ruak’s small People’s Liberation Party (PLP), Fretilin, and the youth-oriented KHUNTO. Fretilin has assumed a number of key ministries from departing CNRT figures.

Various CNRT parliamentary protests and legal challenges to the constitutionality of the reconstituted government, and to the decisions of the President, Fretilin’s Francisco ‘Lu Olo’ Guterres, came to little. Though partisan tensions have been elevated, Dili remains calm as the government has successfully dealt with the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic throughout the year.

The new coalition arrangements mean that aside from a short-lived Fretilin minority government from 2017-2018, Xanana Gusmão is out of power for the first time since 2007. Behind the scenes, it would appear that Fretilin leader Mari Alkatiri outplayed the old master in this round of their ongoing post-independence tussles. Never to be underestimated, the third of the major historic leaders, Jose Ramos-Horta, appears to have informally aligned with Gusmão, a partnership that could see a return presidential bid by Ramos-Horta in 2022. Gusmão is now spending his time party-building, something the CNRT, a classic ‘party of power’ based on Gusmão’s charismatic legitimacy, had neglected since its foundation in 2007. A lot of effort is being put into recruiting support in the powerful Catholic Church and building up district party structures, though the party still lacks a clear second-line of leadership.

But for many in Timor-Leste, as the nation faces an end to its ability to finance national budgets from its oil wealth within a decade, these elite tussles have worn thin. Little progress has been made towards diversifying the economy, meaning the lack of a national consensus over the management of natural resources could undermine Timor-Leste’s long-term economic viability. With existing petroleum funds good for perhaps ten years of annual budgets, a determined effort of consensus-building on policies is necessary to ensure Timor-Leste can sustain the income stream from its offshore oil and gas domains.

By most estimates, Timor-Leste’s sovereign wealth petroleum fund will need to find new revenue by 2030 to support annual budgets of the size the nation has become accustomed to. On average annual budgets have been increasing by 11 percent per year. Despite the prospect of some increased revenue from Santos’s lease in the existing Bayu-Undan fields in Timor-Leste’s maritime zone, there is still no resolution to the key issue of developing the untapped Greater Sunrise oil and gas field.

Political developments in 2020 have created a sense of policy limbo. Championed for so long by Gusmão, and the centrepiece of the National Strategic Development Plan, the Tasi Mane oil and gas processing megaproject on Timor’s South coast is under a cloud, with Gusmão in opposition. The next election is not due until 2023, by which time Gusmão will be 77 years old. In this period, the question of the new government’s policies toward Greater Sunrise looms large.

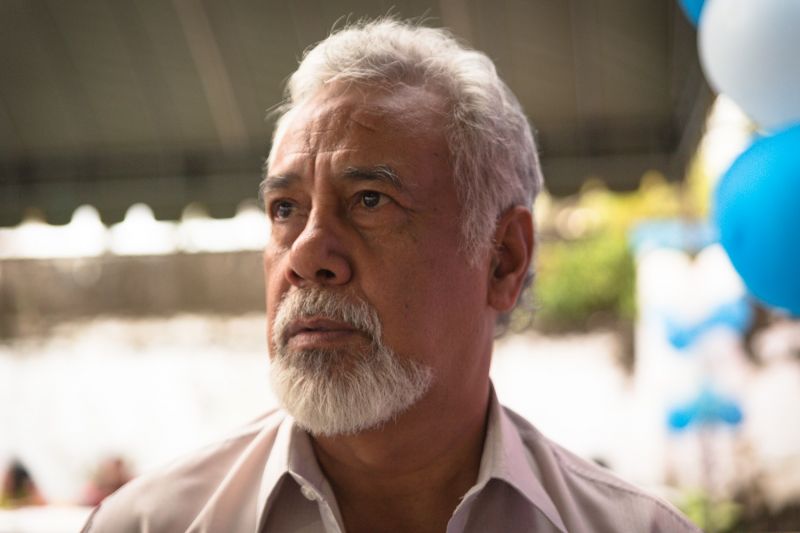

The Tasi Mane oil and gas processing megaproject, championed by former President Xanana Gusmão (pictured), remains under a cloud. Image credit: Isabel Nolasco Photography.

The Tasi Mane oil and gas processing megaproject, championed by former President Xanana Gusmão (pictured), remains under a cloud. Image credit: Isabel Nolasco Photography.

The remodelled government and its new executive have sent mixed messages to date. While PM Ruak recently reiterated his support for Tasi Mane, other members of the executive, including the new Petroleum Minister, have qualified support for the plan by emphasising the need for independent feasibility studies. The government has also replaced longstanding leaders of the National Petroleum and Minerals Authority and the national oil company, Timor GAP – figures who were instrumental to articulating the CNRT’s visions for the industry.

While the Gusmão-led governments promised far larger revenue streams than would be received by downstream processing in Australia, the call for feasibility studies has the backing of some independent analysts. Prominent NGO La’o Hamutuk argues that the “risks, benefits and costs” of downstream processing “have not been seriously analysed”. Illustrating the problem, the 2021 budget proposes to draw down the Petroleum Fund above its sustainable income level by some US$830m, a practice only viable for another ten years on current estimates.

Parliament’s powerful public finance committee has openly questioned the logic of some of the transfers to megaprojects in this year’s budget, given the continuing issue with access to safe drinking water in some communities. La’o Hamutuk has warned of insufficient spending on the government’s stated priority areas of health, education, water and agriculture, which together account for 18 percent of the 2021 budget. This has been a common refrain over the years, and La’o Hamutuk notes the contradiction between the call for feasibility studies and the continuing allocations to institutions like Timor GAP, which next year will receive some USD 70 million.

There is always a good chance Gusmão could resume power by 2023, this time with a friendly President. If so, the current government has perhaps 30 months before it faces elections, and with a presidential election due in May 2022, may have as few as 18 months with a president as supportive of the current government as Fretilin’s Lu Olo has been. But this outcome is no longer the certainty it once was. While Gusmão has proved a master coalition-builder over the years, Fretilin’s core support base of 30 percent is a powerful basis for alliances, and the party appears to be improving its ability to negotiate these. In sum, it cannot be assumed that the current government is merely a placeholder for the return of Gusmão.

The change of government therefore raises a much larger issue for Timor-Leste as a whole. With the future of the Timorese economy at stake, and with CNRT out of power for now, many would argue is it time for a cross-party consensus on the management of the state’s key untapped resource wealth; or at least, an updated debate over the various options for development.

While this may seem a pipe-dream given the political rifts, and it would require technical support, parliament is well placed to conduct an inquiry to establish a cross-party foundation for resources policy. While the operations of Timor GAP have now been referred the National Audit office, what is at stake is far more than a technical matter.

The options confronting government are difficult ones and go to the heart of how Timor-Leste’s major non-renewable asset is managed: Does the government proceed with the existing Tasi Mane vision, or a stripped back version? Does it backfill the oil and gas to Darwin, leading to far lower costs to the state, but potentially lower revenues? Or are there other more innovative options, which take note of the global shift away from fossil fuels? Could Timor-Leste pioneer ways of being paid for not exploiting the Greater Sunrise resource?

The nationalist politics of this issue, tied up with the now-resolved issue of maritime boundaries with Australia, remain potent, despite Gusmão’s move to opposition. While the successful maritime boundary campaign was a powerful nationalist totem, the future management of oil and gas in Greater Sunrise was always a separate issue; with various development schemes still allowable under the terms of the border treaty.

Meanwhile, highlighting the sense of political flux, new smaller parties are rising in Timor-Leste. The next elections could see shifts in the minor players that make up parliamentary majorities. Many might see this as a good reason for Timor-Leste’s major political parties to come together over the management of its major non-renewable asset, and start to plan the next ten years of poverty reduction and economic diversification together.

Michael Leach is Professor of Politics and International Relations at Swinburne University of Technology.

Banner image: Aerial photo of Dili, Timor-Leste. Credit: Jack Nugent, Shutterstock.