The tough strategic choices to secure Australia's future

By James Curran, Professor, Modern History – the University of Sydney

Whoever is sworn in as prime minister after the forthcoming federal election will find little joy in the global and regional outlook.

Either Scott Morrison or Anthony Albanese will confront the stark reality of a world where military hostilities continue to rock Europe and where the possibility of war in Asia and the Pacific continues to be aired by senior political leaders in Canberra and Washington, Tokyo and Taipei.

Yet the slogans that come so naturally to Australian political rhetoric will hardly be put aside. As a serious response to the strategic circumstances, however, their adequacy will be increasingly found wanting. The parliamentary bonfire of early February, in which both sides of politics wilfully torched Australia’s China relationship in a blaze of name calling, has once more revealed how easily Australia’s relationship with its primary economic partner becomes hostage to crude domestic politics.

Beijing is unlikely to care much about the Australian election result, especially since both parties are in virtual lockstep over China policy. Labor believes a softer tone, and presumably a modification of the stark ideological fervour that Prime Minister Morrison has adopted since the middle of last year, will help restore some decorum to the relationship.

But Mr Morrison has public opinion on his side in the stances his government has taken towards China. He has, too, established a new modus operandi with the United States, making Australia arguably the most loyal and reliable ally Washington has in the region. More than at any point since the Second World War, Canberra is tightly tucked into the enveloping embrace of American Asia policy.

Labor promises more diplomacy, a re-energised Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and an ear more acutely attuned to how partners in Southeast Asia are managing China. But, absent a swift and brutal clearing of the bureaucratic stables, Mr Albanese will find himself surrounded by the same high profile intelligence officials who have dominated Australia’s response to China. And he is locked into the arrangements — especially AUKUS and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) — which have reinforced Australia’s impulse to face an uncertain world together with its longstanding cultural and political allies. Because Labor will want to establish quickly its national security credentials so as not to be dubbed weak, there will be little appetite for much moderation or policy review.

Given that China’s economic coercion of Australia continues, even the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of formal Australia-China diplomatic relations in December may not prove the circuit breaker some might aspire for it to be. But at the very least Canberra could emphatically use the occasion to celebrate the contribution of the Chinese-Australian community to the social and cultural fabric of national life. This would help make up for the glaring failure to do so at times in the past two years when the loyalty of Chinese-Australians has been insultingly brought into question.

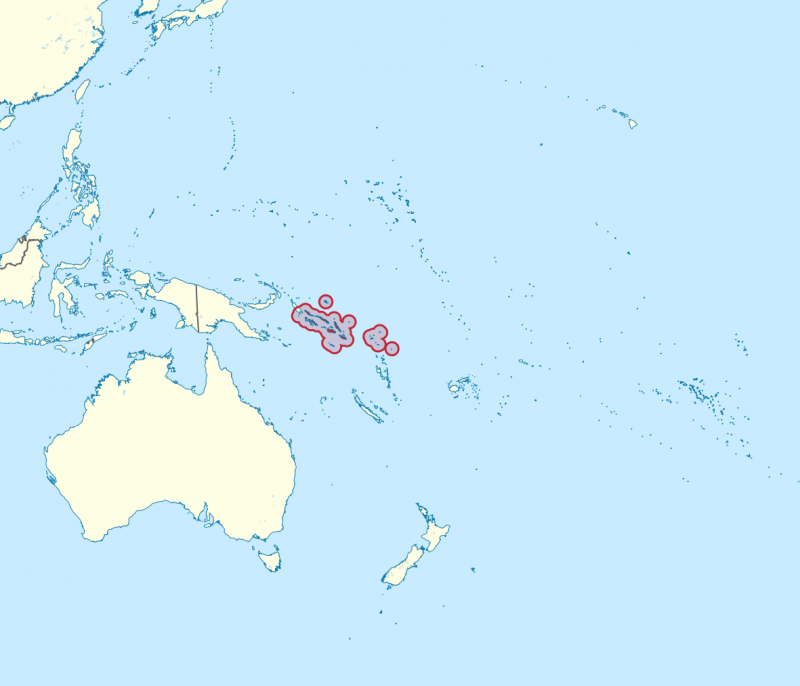

But whoever wins government, their most immediate concern will be the fallout from the signing of the security agreement between China and the Solomons Islands. With the failure of American and Australian efforts to dissuade Prime Minister Sogavare from inking the deal, the security agreement — and its uncertain implications — has only underlined just how much a creative reset is required in Australian thinking about its relations with neighbouring countries. The prospect of a Chinese military foothold of this kind is profoundly disturbing, touching as it does on the fears that have animated policymakers since the colonial era: a foreign power occupying a strategic launch pad in the Pacific. Beijing’s move is a measure of how much more intimidatory it has become since 2018 when Mr Morrison took over from Malcolm Turnbull.

The Solomon Islands, highlighted and magnified, is a close Pacific neighbour of Australia. Image credit: Wikimedia.

The next government too will be responsible for taking AUKUS to its next phase, a grouping which, along with the Quad leaders’ forum, will be viewed more and more by Beijing as an outright containment strategy. It is passing strange that at no point since the original announcement has the government sought to explain in any detail how this vast national endeavour, stretching out over the next two decades, is actually going to work. But what will have to start too is the brutal task of levelling with the electorate about the need for greater military spending. And that will require spelling out the painful reality of where the money will come from.

It should also mean a more sustained, critical debate over the implications of AUKUS for Australian freedom of policy movement. Senior intelligence officials stress that Australia retains agency, but that needs further explication. Canberra has committed itself to a US agenda in Asia whose objectives are still not yet clear. Indeed, Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith suggest a pressing need “to accept in our strategic thinking that America is now a more inward-looking country that will foreseeably give more attention to its domestic social and political challenges”. A better-funded DFAT, with its status and primacy in foreign policy planning restored, could assist in thinking through how Australia might deal with an America whose internal challenges may continue to qualify the extent and scope of what it is capable of fulfilling abroad.

The United States has been praised for its success in generating broad international support for financial and economic sanctions against Russia over the invasion of Ukraine. But it would be a mistake to equate this with widespread vindication of Mr Biden’s framing of the world situation as a new ideological contest between autocracies and democracies. One need only consider the stances taken by New Delhi and Jakarta to see how limited that framework is for a complex world.

Nevertheless, the Biden administration has pressed ahead with its Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, the optimistic tone of which, as Mary Lovely has recently argued for the East Asia Forum, “obscures a precarious assumption underlying the strategy, that partners in this endeavour share the American desire to build China out of regional economic and technology networks”. For all the justified concern in Southeast Asia about Chinese aggression and coercion, Lovely adds, it is doubtful they agree with Washington’s view that China “can or should be excluded from regional economic and decision-making forums".

Despite the justified confidence in America’s ability to quickly marshal allies and partners behind its sanctions policy over Ukraine, the new Australian government will likely deal, too, with a weakened Biden administration after what may well prove a demoralising result for the Democrats in the mid-term elections this November.

That will only strengthen the voices in Washington arguing for a tougher stance on China and a surer commitment to the defence of Taiwan. The Ukraine crisis has also given some in Washington that feeling of what it is like to lead again. That has meant the revival of the same ambitious streak in American foreign policy thought which led to the strategic disaster of the Iraq war. “It is now the case,” argues the editor of The National Interest, Jacob Heilbrunn, “that a belief in the unabashed assertion of American power abroad, democracy promotion, and regime changes is once more gaining sway.”

If the past four to five years have been challenging for Australian foreign and defence policy in managing China, the next will be harder. The discipline of the Biden administration in resisting the policies and intellectual environment of a new Cold War will be sorely tested. Then, within the next term of the Australian electoral cycle, the prime minister will need to deal with a United States conceivably led from the White House by Donald Trump himself or a Trumpian figure in his image. And it is possible that this would follow a tightly contested presidential election, with the potential for yet more domestic disarray in the United States. The inescapable reality, however, is that despite these internal challenges, both sides of politics in Canberra have banked the strategic house on American resolve in resisting China. China has become for the US Alliance what it was at the height of the Cold War: the bond that binds in the Pacific.

James Curran is Professor of Modern History at the University of Sydney. His new book, Australia’s China Odyssey, is published by NewSouth Press in August.

Banner image: HMA Ships Arunta and Canberra in the South China Sea during the Regional Presence Deployment 2020 - July 17, 2020. Credit: ADF Image Library.

This article was contributed as part of an Asialink Insights series on the China policy challenge facing Australia, 'China: the road ahead'.