The Philippines Presidential Elections: a story of duelling legacies

By Reynaldo Ileto, Honorary Professor, Emeritus Faculty member – School of Culture, History & Language, the Australian National University (ANU)

The 9 May election in the Philippines is capturing worldwide attention because the likely winners of the presidential and vice-presidential races are children of presidents with an unsavoury reputation in the global press. The presidential frontrunner, with around 58 percent of the vote compared to the 22 percent of his closest competitor, is Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the son and namesake of Ferdinand Marcos, president from 1965 to 1986. The elder Marcos is often called “dictator” for having ruled by decree under martial law from 1972 to 1981. He was ousted in February 1986 by a peaceful uprising that installed Corazon Aquino as president.

Bongbong Marcos, or “BBM” for short, is teamed up with vice-presidential bet Sara Duterte, the current president’s daughter and the mayor of Davao City. Inday Sara, as the public affectionally calls her, has a similar popularity rating to BBM’s as she prepares to face the separate election for vice president. The team’s impending victory will effectively result in a continuation of the Duterte administration’s policies. BBM has repeatedly made assurances to this effect. Moreover, Sara’s election will position her as the likely successor to BBM and place in high office another former mayor, as her father had been for over 20 years.

The election is being pitched to the outside world as the archetypal battle between democracy and authoritarianism. For Australian observers, this has been the conventional lens for viewing political change in neighbouring countries. For the past six years, the Duterte government has been portrayed in the media as authoritarian and populist. Duterte’s seeming empowerment of the executive arm of the state to the detriment of the judicial and executive arms is portrayed as evidence of democracy’s decline. Duterte’s “war on drugs” is condemned as the displacement of the rule of law by the rule of violence.

What is worse is that Duterte did not subscribe to the conventional discourse about the “dictator Marcos”. Three months into office, he implemented the Supreme Court’s decision to allow the burial of the dictator, who had died in 1989, in the Cemetery of Heroes. The link between the Duterte presidency and that of the late dictator was formally established. The BBM-Sara team that appears to be headed for victory can thus be portrayed as the harbinger of dark times.

This is not the way the Filipino voting public sees things, judging by the polls and the massive turnouts in BBM-Sara rallies and motorcades. And this is the problem. For the potential losers in the election there is puzzlement, disdain and anger at the voting public’s seeming acquiescence to Duterte’s anti-democratic practices and, worse, its failure to understand the dire consequences of a return to the “dark age” of Marcos rule. Should we subscribe to this view as well, or should we delve deeper into what is going on beneath the surface?

Perhaps this is not a poll over democracy, but rather the outcome of an ongoing clash of political narratives over the past 50 years. Perhaps what is at stake is the truth about the martial law era under Ferdinand Marcos beginning in 1972 and the so-called People Power revolution in 1986 that took down Marcos and installed Corazon Aquino as President.

Marcos represents dictatorship for having grabbed power in 1972, while Aquino represents democratic revival from 1986 onward. The narrative of a descent into a dark age of despotism upon Marcos’s declaration of martial law in 1972 leads to a redemptive event: the assassination of opposition leader Ninoy Aquino in 1983 and the victory of his widow Cory in a show of People Power in 1986. Thus, the tyrant Marcos is driven out and democracy renewed.

What is missing in this narrative is the wider context in which these events took place. The year 1972 brings us back to the Cold War era when military or authoritarian rule was commonplace throughout the Third World. Marcos was anointed by the US to the leadership of the former American colony. A question rarely asked is how Marcos performed in comparison with Suharto, Lee Kuan Yew, Ne Win, Park Chung-hee, Mahathir Mohamad, Nguyen Cao Ky and other Asian autocrats of that era.

By 1986, the Cold War was nearly over, the era of globalisation was emerging, and democratic restoration was the new American buzzword. Marcos was unseated by a military coup under the cover of a “nonviolent” urban uprising — the first “colour revolution” in Asia — supported by the Catholic Church and the US Embassy.

An armed forces full honour departure ceremony is held for then-President of the Philippines Ferdinard E. Marcos following Washington talks with then-US Secretary of State, George Shultz - September 20, 1982. Image credit: US Department of Defence.

In recent decades, the dominant narrative of a dark age of dictatorship under Marcos has been eroded by the uncovering of new information about what had really happened in the 1970s and 80s. The alignment of Filipino political forces with shifting US foreign policy was particularly noted. As the US moved towards globalism, Marcos insisted upon following a nationalist trajectory of development prioritising industrialisation and self-sufficiency in food and energy. There is overwhelming evidence that his removal was directed from Washington.

The public, largely through social media, is increasingly aware of alternative readings of the narrative of Marcos’s rule. Whilst the image of Imelda’s hoard of shoes may still shape Western perceptions of the Marcoses, most Filipino voters now know that those shoes were mostly gifts to the First Lady from the shoe manufacturers of the town of Marikina, whose entry into the world market was facilitated by the government.

Whilst the opposition continues to taunt BBM as the “son of a thief”, it is an open question as to whether the elder Marcos had looted the treasury or, as claimed by the family, possessed wealth of his own even before becoming president. Numerous cases of plunder against the Marcoses have been filed in Philippine and US courts but most have not prospered for lack of evidence. The central mystery revolves around Marcos’s apparent discovery and possession of much of the gold left behind by the fleeing Japanese in 1945.

The triumphalist narrative of democracy restoration in 1986 has also been contested. There still are unanswered questions. For instance, who ordered Ninoy Aquino’s assassination? In the 12 years that Cory and her son Noynoy Aquino III occupied the presidency, there was a lack of urgency in discovering the truth. Furthermore, Cory Aquino’s presidency did not fulfill post-People Power expectations of an age of prosperity. Energy and food security, peace and order, and industrial development declined. Democratic reform did not lead to a better life for the average Filipino.

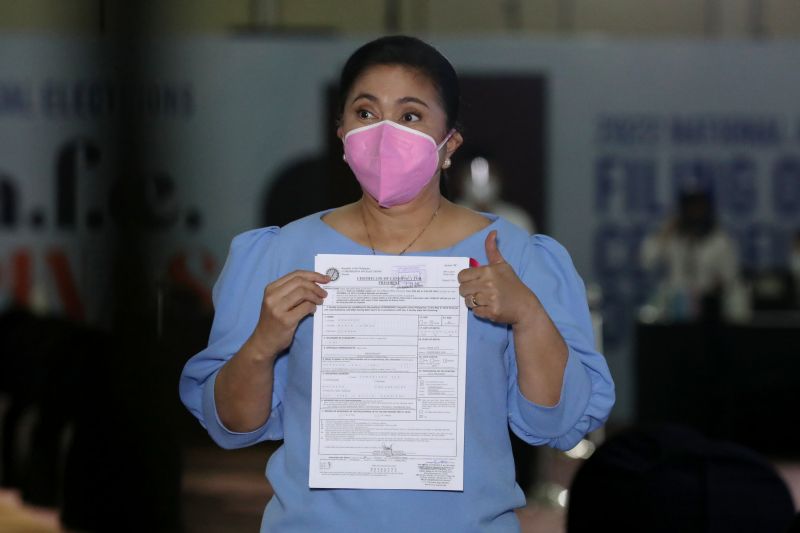

Vice President of the Philippines, and leader of the Liberal Party, Leni Robredo files her candidacy for the 2022 Presidential Election, Pasay City, the Philippines - October 7, 2021. Image credit: Joey O. Razon, Philippine News Agency.

BBM’s only real opponent is Vice President Leni Robredo, leader of the Liberal Party, which seemed invincible when Noynoy Aquino III was President from 2010. Robredo was Noynoy’s anointed candidate for Vice President in 2016 – a race she won over BBM by a small margin. Today she is fighting for the survival of the 1986 narrative of Democracy Restoration through People Power. She has waged a negative campaign on the theme of preventing another Marcos from casting the country into another dark age, but the strategy has backfired.

The blame for the voting public’s support for the BBM-Sara duo is placed on the elder Duterte. The vigorous public debates over whether the late dictator should be buried in the Cemetery of Heroes served to heighten public consciousness of an alternative history of the Marcos years that had been swept under the rug by the democracy narrative of the 1986 People Power uprising.

Perhaps the forthcoming election is less about democracy than about the future of the Philippines in a changing world order. The descendants of the 1986 ‘revolution’, as if acting in concert with the US pivot to Asia, loudly contested Duterte’s every move to strengthen diplomatic and economic ties with China. Duterte astutely recognised the implications of the rise of China as a global economic power and potential regional hegemon. He battled with the widespread perception among the public, stoked by his predecessor Noynoy, that China was the aggressor in the South China Sea conflicts, and he largely prevailed.

Strengthening ties of friendship with China and Russia was the natural offshoot of Duterte’s attempt to push back on the immense influence that the US has had in Philippine foreign policy making, particularly under the previous government. Duterte’s speeches during his first year in power were often dotted with history lessons, notably his resurrection of the “forgotten” Filipino-American War of 1899-1902. He reminded the nation as well as the world that the US had come to the Philippines as an aggressor that committed atrocities against both Christian and Muslim Filipinos who resisted the American takeover. The US destroyed the first Republic founded in 1898, and from 1901 to 1946 gradually transformed the Philippines into a friend and ally.

The US-Philippines special relationship was tested in WWII and the Cold War and seemed to be set in stone. But Duterte believes that the world has changed since the Cold War, and that the blind continuation of the special relationship could only bring disaster. He repeatedly states that the country would be crushed like an ant in a fight between the American and Chinese giants. Upturning his predecessor’s policies, Duterte insisted that the Philippines would side militarily with neither power. Recognising China’s rapid wealth growth – in contrast to America’s financial woes and de-industrialisation – the economy would be firmly hooked onto China’s Belt and Road initiative.

Over the years, Duterte has had to retreat somewhat from his ambitious goal of an independent foreign policy. The special ties with the US are too deeply embedded to be broken precipitously. There are pro-Americans even within his cabinet and certainly in the military. Anti-Chinese sentiments continue to linger in society and can be easily stoked by slanted media reports of incursions in the Spratlys. Joint exercises between the American and Filipino armed forces continue to be held annually, with China as the implicit adversary. The Duterte government, however, has clearly succeeded in steering the public mindset away from the 1986 Aquino narrative of banishing the tyrant Marcos, restoring democracy, and realignment with US policy in the world. Thus, we ironically see in the coming elections the return of a form of “people power” that now is anathema to the former colonial master and the Church.

The fear among the US and its allies is that a victory of BBM and Sara will mean a continuation of Duterte’s initiatives. BBM has made it clear that, while acknowledging the deep historical ties with the US, he will not revert to Noynoy’s policy of leading the charge against China. This is the opposite of how Australia views the problem, and so the gap between the Philippines and Australia can only widen further. The election has not yet taken place, however. The fear among the supporters of BBM-Sara, and the Duterte government itself, is that something unexpected might happen that will derail the present course of events.

Reynaldo Ileto is Honorary Professor, Emeritus Faculty member, School of Culture, History & Language at the Australian National University.

Banner image: Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr. and vice presidential running mate Davao City Sara Duterte wave to crowd during campaign appearance, Quezon City, the Philippines - December 8, 2021. Credit: Joey O. Razon, Philippine News Agency.