Making What Was Hard Harder: the Trump Administration and Southeast Asia

By Malcolm Cook, Visiting Senior Fellow, at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore

Last Thursday and Friday, Mike Pompeo likely made his last trip to Southeast Asia as US Secretary of State. It was as unspectacular as it was brief. In New Delhi, the first leg of Pompeo’s whistle-stop Asian tour, an important agreement to deepen US-India military ties was signed. Pompeo’s final stops in Jakarta and Hanoi offered no deliverables of similar status.

Pompeo’s two days in Southeast Asia highlighted the hard road the US faces in the region in relation to its growing rivalry with China, and how Trump administration diplomacy, rhetoric and policies have made it harder. Whether Trump is re-elected or Joe Biden replaces him tomorrow, the next US administration will find few like-minded states in Southeast Asia willing to actively cooperate with the USA to push back against China’s growing influence and aggression.

The preceding Obama administration showered an unprecedented amount of attention on Southeast Asia and ASEAN. Despite this, rallying Southeast Asian support in America’s rivalry with China, or even against Chinese unlawful aggression in Southeast Asia itself proved difficult:

Three elements of Pompeo’s visit to Hanoi and Jakarta highlight how the Trump administration has made this Southeast Asian strategic problem for the USA worse.

First, the preparations for this trip were far from smooth. Indonesia was supposed to be the only Southeast Asian country Pompeo would visit only days after Indonesia’s Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto’s norm-breaking visit to the USA. Yet, at the last minute, when Pompeo was already in Asia, his visit to Vietnam was announced. Vietnam, along with Singapore, has worked much harder than Indonesia to engage with the Trump administration and is more like-minded with the US in balancing against China than Indonesia and the Jokowi administration.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo speaks with US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Jakarta, Indonesia - October 29, 2020. Image credit: US Department of State, Flickr.

That this very late-in-term trip was Pompeo’s first visit to Southeast Asia for primarily bilateral reasons, Vietnam was added at the end, and Singapore was excluded reflect the Trump administration’s lack of sustained high-level engagement in Southeast Asia (and vice versa). According to State Department press releases, only one Southeast Asian (the foreign minister of Laos on 28 June 2020) was among the 142 bilateral or minilateral meetings Pompeo had with foreign leaders from 4 November 2019 to 5 October 2020.

President Trump has spent more time preparing for and travelling to Southeast Asia to meet North Korea’s young demagogue Kim Jong-Un than he has for meeting Southeast Asian leaders. Indian prime minister Narendra Modi likely has had more face time with President Trump than all serving Southeast Asian leaders combined. According to White House press releases, President Trump has met only one Southeast Asian leader in the last 18 months, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in New York in September 2019. Southeast Asian officials routinely criticise the US for not showing up enough in the region. Over the last four years, this criticism has been true both ways.

Second, the Trump administration’s increasingly virulent anti-communist and anti-China rhetoric grates with Southeast Asians. In his major speech in Jakarta to the youth wing of Indonesia’s largest Islamic movement, Nahdlatul Ulama, Pompeo labelled the Chinese Communist Party the greatest threat to religious freedom and urged Indonesian Muslims to speak out against China’s inhumane treatment of Uighurs. Nahdlatul Ulama is unlikely to see the Chinese Communist Party as a great threat. The movement’s chairman Said Aqil Siradj argued last year that China and Indonesia “could never be divided because they shared the same perspective on the history of Islam”.

In its Twitter feed on Pompeo’s visit to Hanoi, the State Department, without irony apparently, cited Pompeo (referencing China) that “Communists almost always lie”. Undoubtedly, his Vietnamese Communist Party hosts would beg to disagree. This tweet has since been taken down. One does not wonder why.

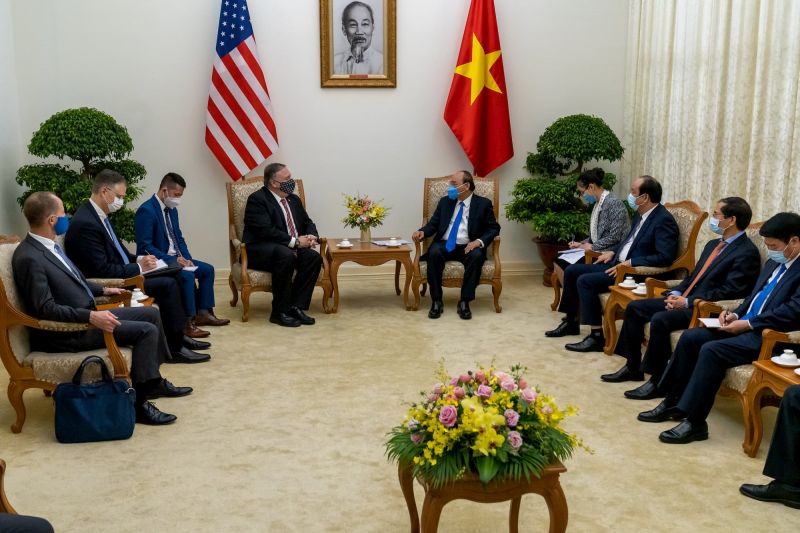

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo meets with Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc in Hanoi, Vietnam - October 30, 2020. Image credit: US Department of State, Flickr.

Finally, Pompeo came to Indonesia and Vietnam with many fewer economic offerings than Japan’s new prime minister Yoshihide Suga did the week prior, and much less than those of his Chinese rivals. Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported that Suga came to Jakarta with a 50 billion yen (US$477 million) concessional loan to help Indonesia’s COVID-19 response and 4.4 billion yen (US$42 million) in grants to Indonesian medical research institutions. The largest dollar figure mentioned in the State Department press releases reviewing Pompeo’s trip was $2 million in new assistance to help Vietnam recover from recent major flooding.

The Japanese government has offered Southeast Asian states the US$110 billion Partnership for Quality Infrastructure as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. By some estimates Japan still is sending more dollars to finance infrastructure in the region than China. The Trump administration has nothing similar to offer.

If the next administration in Washington wants to arrest the loss of influence in Southeast Asia, its leaders should visit Southeast Asia more often, stay longer, offer more economically, and say less against communism and China.

Malcolm Cook is Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore. He was the inaugural East Asia Program Director at the Lowy Institute where he remains a non-resident fellow and former Dean of the School of International Studies at Flinders University of South Australia.

Banner image: US President Donald Trump and Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc are greeted by schoolchildren, the Office of Government Hall, Hanoi, Vietnam - February 27, 2019. Credit: The White House, Flickr.