(Liberal) Paradise Lost: What Went Wrong for Politics in Hong Kong

By Michael DeGolyer, Former Professor, Political Economy, Government and International Studies at Hong Kong Baptist University

The promulgation of laws against sedition, subversion and secession by China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) imperils Hong Kong's neo-liberal political economy.

Hong Kong and neo-liberalism met in the books of Milton Friedman. Friedman asserted Hong Kong's low-tax, small government, laissez-faire, low regulation approach created a liberal paradise.

The virtually untrammelled freedom to pursue one's interests and government's focus on maintaining the framework for this, via the rule of law and as little interference as possible in people's lives, led to disinterest in politics as people got on with what really interested them – bettering their economic condition. To Friedman, Hong Kong embodied the belief "that government is best which governs least."

His ideas led Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher—she who negotiated Hong Kong's handover to the People’s Republic of China—to lead a movement to shrink government by cutting both its revenues and its services, and a movement to focus the world on freeing trade in order to promote the only freedom they believed really mattered.

These ideas lay squarely behind the notion that as long as the technocratic administration of Hong Kong stuck to this framework, and mainland China did not interfere, then all would be well. There was little cause to worry overmuch about developing political leadership, as that was not really needed.

Rising political dissent since 1997 has changed the plot from Milton Friedman's neo-liberal paradise to that other Milton's: Paradise Lost. Satan—strife over political power—has entered and is displacing Hong Kong people from the liberal paradise bequeathed them.

Friedman (and Reagan and Thatcher) misunderstood what made Hong Kong tick.

Indeed, they got the meaning of the phrase "that government is best which governs least" wholly wrong. The origin was in Henry David Thoreau's On Civil Disobedience, published in 1849, inspired by the wave of democratic revolutions in 1848 (the same revolutions that inspired Karl Marx – whose ideas led to mainland China's revolution).

Those 1848 "liberal" revolutions stemmed from revolt against government suppression of politics and refusal by elites to end their monopoly on power and wealth. That kind of government—the repressive, monopolistic kind—governed best when it governed least, that is, when it intervened least to stop popular leadership being able to address popular demands to open up economic and political power. That meaning of the phrase as opposing government intervention to protect monopolies applies to Hong Kong, not the misinterpretation by Friedman.

Historically, when issues demanded the colonial administration head off rising dissent, colonial officials would take bold action quite in contrast to Friedman's mythic laissez-faire ideas.

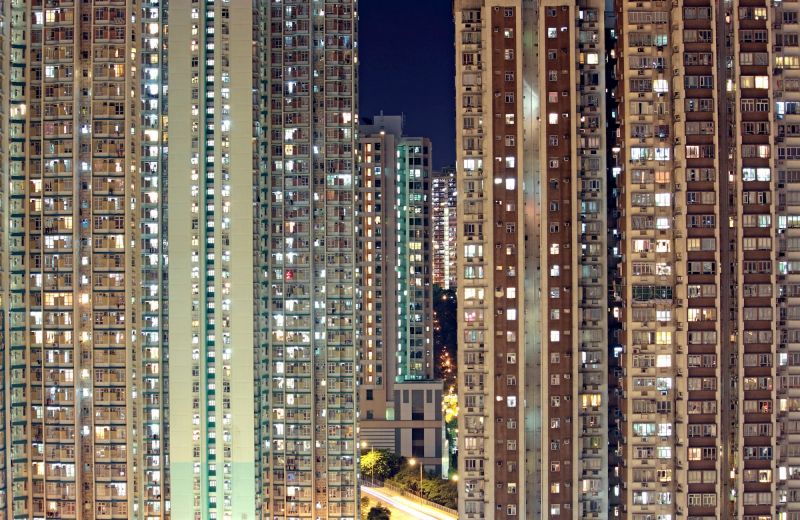

The public housing program that led eventually to over half the population living in government subsidised housing arose from disastrous fires in the "temporary housing" camps. The need for public housing—driven by community demand—led to the "new towns" program wherein Hong Kong officials created new cities on new sites.

Hong Kong public housing. Image credit: cozyta, Shutterstock.

The need to do that, including planning and provisioning for schools, hospitals, and social services, led them to craft ways to direct and subsume political mobilisation and organising into means to both provide the services demanded and to control the groups demanding them.

Government "subsidised" and supervised services from "charitable and community" groups, which in turn would organise communities that needed services. The need to coordinate and monitor those community groups, and to assess which groups needed more or less subsidisation to meet current community demands, led the "laissez-faire" government to set up "mutual aid" groups in the new towns and public housing estates. These worked so well the colonial government extended its "social administrative organising" into the private estates with the district board system.

The British turned over much of the supervision and allocation of local community public services to the Urban and Regional Councils, which in turn got power to lay modest taxes and users fees on such services and amenities. These councils mediated public complaints about local civil service-provided facilities such as rubbish collection, parks and recreation and public toilets by having these locally elected officials explain policies and costs to their constituents as well as convey complaints to civil servants. Politics— determining who gets what by non-market means—became an aspect of administration.

What went wrong after the British left? What Friedman missed is that British officials held power tenuously. They knew they could not put down dissent by force, and even if they tried, China would intervene.

Colonial officials had to build a system attuned to monitor popular discontent and acutely attuned to act to direct and subsume that discontent into programs and policies that placated restiveness. They strongly encouraged their Chinese civil servants to be frank, and they handsomely rewarded those who proved most adept at heading off trouble.

Big business had an interest in cooperating for they too did not want popular dissent to lead to Maoism. Business under the British until the early 1980s focused on global and regional trade since open trade with China was not profitable until Deng Xiaoping consolidated power.

Aerial view of Hong Kong and Victoria Harbour. Image credit: EarnestTse, Shutterstock.

To pay for all this, Hong Kong developed a hidden taxation system from land leases and control of transport systems and what became the world's largest commercial property portfolio that produced more revenue than its "simple and low" open tax system did.

In 1997, the British simply handed Hong Kong over to its business and civil service elites, with China's blessing. Both expected the compact between these groups to preserve the "liberal paradise" left them. The Functional Constituencies dominated by business offset the Geographical Constituencies dominated by Hong Kong's infant popular parties. They expected civil servants would play off business and popular sentiment against each other and maintain a balance and thus control.

But the dynamic that produced sensitivity to restiveness and that focused on international connections in order to thrive in business began to disappear.

Instead, more of the business elite felt business with mainland China was far more important to them than global competition. They increasingly looked to party connections as a means first to enter China, but then, increasingly, as a lever to control both Hong Kong's civil servants and its populace, as both grew restive under increasing exploitation and frustration.

Hong Kongers found it difficult, if not impossible, to compete with the major hongs (conglomerates) as government gave up any effort to regulate monopolies and break up cartels. Government, dominated by business that wanted its costs reduced, shrank expenditures, stymied government initiatives, "privatised" housing and commercial properties and transport, and put social and medical services on block grants – stepping away from cooperative supervision.

The mutual aid societies in public housing estates received benign neglect and withered away. The Urban and Regional Councils were abolished. Political representative structures were reduced to talking shops with no real power over much of anything. The civil service increasingly became mainland shoe shiners and supervisors running poorly paid contract staff. The staff's only real interest was either getting on permanent terms or getting out of administration altogether. Alerting superiors to trouble became a liability, not a means, to promotion. Restiveness grew unabated and unmonitored until trouble began to explode in the streets, over and over.

Rather than co-opting critics into helping to solve problems that sparked the rise of the protest movement, post-colonial government increasingly sought to ignore, intimidate, then silence and now jail them. That the NPC will promulgate a law empowering local government to act more aggressively to silence its critics, and that this specifically violates the negotiated agreement that Hong Kong "on its own" would implement such laws (Article 23 of the Basic Law) is but a culmination of processes underway since 1997.

Democracy has "people power" as its slogan, but in reality democracy required leaders to strike compromises and persuade followers that the attainment of people power might require detours along the way, and in the case of Hong Kong, had to be achieved under an illiberal, one party dictatorship.

Armed riot police face protestors rallying against the 2019 Hong Kong extradition bill - June 12, 2019. Image credit: May James, Shutterstock.

This was a task demanding considerable political skill and high legitimacy. It required the taming of elites unwilling to share power and wealth. But China's one-party dictatorship viewed the development of such "political" leaders as a threat, as did the entrenched civil service and business interests.

Mainland China's princes, who inherited their positions, increasingly dominate the party and China, monopolising power and wealth and shutting off opportunity. While popular demands for access and opportunity have yet to reach explosive levels on the mainland, Hong Kong's more exploited and repressed population have hit and stayed at a boiling point for years, to the point the mainland feels, perhaps rightly, it has no choice, if it wishes to maintain control, other than to crack down and suppress Hong Kong's liberal revolution.

But Thoreau and Marx concluded from the 1848 popular uprisings that political-economic monopolies lead to revolution. As Adam Smith noted too, big business conspires together to fix markets and control governments, stymying innovation and competition.

If government becomes not a form of containing discontent by obtaining public consent for programs, policies and administrative initiatives, and instead becomes a monopoly on power protecting a monopoly on opportunity, it turns septic, frustrating and eventually, destructive.

It might suppress revolution for a time, but it’s very actions foster rebellion. The NPC's intervention will not solve Hong Kong's problems of governance; it will only make them worse. That kind of government— the repressive, elite dominated, elite protecting kind—is best which governs that way least.

Instead, Hong Kong and China, and for that matter the US and UK, could learn from South Korea about how to move toward democratic liberalism, and thus end protests and revolts by breaking monopolies on power and wealth.

Michael DeGolyer was Professor of Political Economy, Government and International Studies at Hong Kong Baptist University from 1988 to 2015 and the former director of the Master of Public Administration Programme jointly offered by HKBU and Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.