Kishida’s perilous road ahead

By Purnendra Jain, Emeritus Professor, Department of Asian Studies, University of Adelaide,

and Takeshi Kobayashi, Member, Liberal Democratic Party; Former Staffer, Masahiso Sato MP

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida won a landslide victory in the upper house elections held last month, two days after former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s brutal assassination while campaigning for the election. This might have resulted in some sympathy votes for Kishida’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) delivering the party far more seats than predicted. However, in the aftermath of Abe’s death, Kishida faces political woes that continue to trouble him. Even a cabinet reshuffle, which normally boosts prime ministerial popularity,has not worked for him. The road ahead for Kishida is bumpy.

Religion-Politics Mingle: The Unification Church

The mingling of religion and politics in Japan is not uncommon. The ruling LDP’s junior coalition partner Komeito is a political arm of a Buddhist organisation, Soka Gakkai with some 8.3 million households in Japan and branches all over the world. Komeito wields significant policy influence which reflects Soka Gakkai’s basic tenets such as human welfare, global peace, and its anti-nuclear stance.

But Abe’s assassination produced a disturbing revelation about a religious group connected to many politicians. The suspect assassin, Tetsuya Yamagami, has stated that his family was bankrupted because of her mother’s membership of the Unification Church, which made her donate excessive amounts of money. The assassin further affirmed that he held grudges against Abe who he claimed had close ties to the Church. While the Komeito-Soka Gakkai ties are well known, little was known about the Unification Church and its connections to the political world until Abe’s assassination.

Stories about the political reach of the Unification Church, officially known as the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, began to pour into national and international media outlets. Since the Church’s establishment in 1954 in South Korea and its first international branch in Japan in 1959, some high-profile Japanese politicians seem to have had deep links with the Church, including Abe’s father Shintaro Abe, Japan’s foreign minister in the 1980s, and his grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, Japan’s prime minister in the late 1950s.

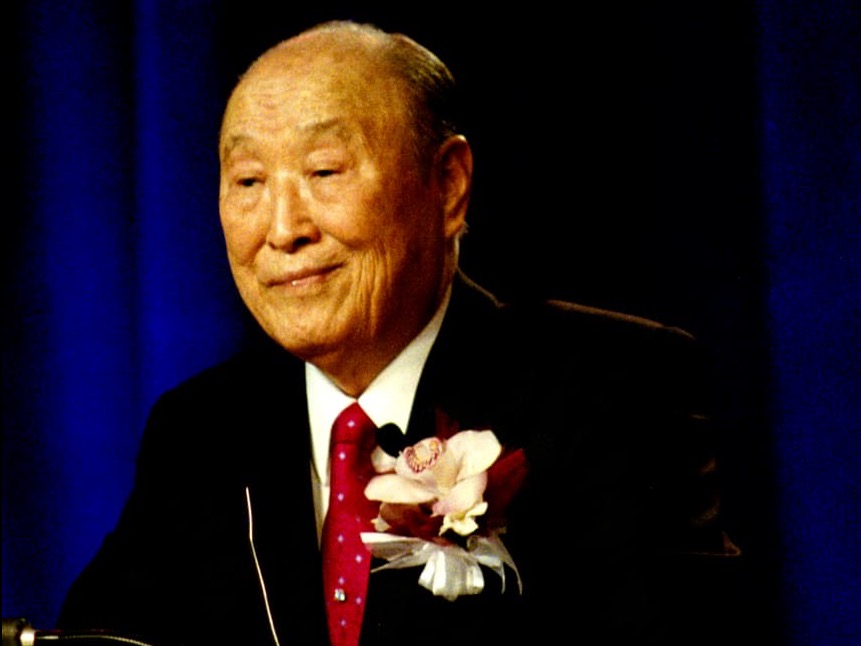

Controversial founder of the Unification Church, the late Rev. Sun Myung Moon, speaks to followers in Las Vegas, US - April, 2010. Credit: Wikimedia.

In addition to its controversial beliefs, the Church also espoused an anti-communist stance at its establishment. This attracted some conservative Japanese politicians. In more recent years, the Church and LDP politicians have held shared stances on highly controversial policy matters, such as their anti-same-sex marriage and pro-constitutional amendmentviews.

Kishida has denied any organisational connection to the Church, but his explanation has not satisfied the Japanese public, with one poll suggesting that 85 percent want politicians to sever their ties with the Church. The current Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi has admitted to ties to the Church, although has promised to end them. New Internal affairs minister Minoru Terada, and ministers Daishiro Yamagiwa and Katsunobu Kato, also have links to the Church.

Factional Balance

Kishida’s popularity was already sagging in late July and one tactic often employed by prime ministers is a cabinet reshuffle to get rid of controversial or unpopular figures and replace them with those who might give a fillip to the party and cabinet.

The prime minister was very mindful of the public perception of his government while selecting ministers and tried to eliminate ministers directly connected to the Church. At the same time, he had to be cognisant of one key organisational element that has dominated LDP politics since itsestablishment in 1955, that is, representation of factions and groups in the cabinet in proportion to their strength in the party.

Currently the LDP has six factions, three groups, and oneloose group of parliamentarians with no designated leader. The Abe faction is the largest with 99 members, while Kishida’s is number four with 46 members. Former Prime Minister Suga runs his own group with 20 members and the unaffiliated group has 37 members. In Kishida’s new cabinet five factions and the unaffiliated group are represented, but other groups, including Suga’s, did not get a place.

Seven ministers who declared their links to the church, including defence minister Nobuo Kishi, were removed while key inclusions were the return of Taro Kono, who unsuccessfully ran against Kishida for the party presidency last year, as digital minister, a much diminished position in the hierarchy for a senior party member who had previously held the defence and foreign portfolios. Kishi was replaced by Yasukazu Hamada, unaffiliated, who returns to the post after a hiatus of more than a decade when he was defence minister under the Aso government (2008-2009). Another unaffiliated, firebrand conservative Sanae Takaichi joins as economic security minister, after serving as party policy chief in the first Kishida cabinet. Notably Takaichi also ran against Kishida for the LDP presidency, supported by Abe, and remains committed to many of Abe’s policies, including constitutional amendment, especially Article IX, the so-called peace clause.

How long this cabinet will last is anyone’s guess as there might be realignment and reorganisation of factions in the aftermath of Abe’s death, affecting cabinet composition. Moreover, the cabinet reshuffle has not given Kishida any reprieve as polls conducted immediately after the new cabinet was announced have given it the thumbs down, with the support for the government sliding to 51 percent from 57 percent taken just before the cabinet announcement. Only 45 percent rated the new cabinet as satisfactory while 34 percent did not think so.

Policy Challenges

There are some immediate policy challenges facing Kishida’s new cabinet. As polls suggest, the economy and inflation, pension and social welfare, education and child rearing support are the top three concerns followed by defence and security. In place of Abenomics, Kishida has his own brand of an economic recovery plan called ‘new capitalism’, but this product has not brought any tangible results so far, as noted by analysts.

On defence and security, the new defence minister has his work cut out. Hamada has to not only secure bigger defence spending, which the LDP and Kishida support, but he is alsotasked with completing a revised national security strategy paper, first put in place in 2013, and the National Defence Program Guidelines and Medium-Term Defence Program by the end of this year.

Given heightened security tensions in the region following China’s live fire drills directed at Taiwan, during which several missiles landed in the Japanese Exclusive Economic Zone, the pressure to boost Japan’s defence capabilities has multiplied several fold. In the past, the Japanese public opposed removing the one percent of GNP ceiling on defence spending, but now there is an appetite for a significant increase. Whether Japan can move towards spending as much as two percent of GNP on defence in the short-term is doubtful, both because of a tight budget and the cautious approach of the Komeito.

The Road Ahead for Kishida and the LDP

A few weeks ago, the Japanese media coined the term ‘three golden years for Kishida’, meaning Kishida will continue as prime minister until 2025 as there are no national elections due. But this narrative has disappeared in recent days. The possibility of Kishida continuing beyond his current term as party chief expiring in 2024 seems dim. His own faction is small and his key supporter Abe is no more. Although Kishida and Abe differed on some policy issues, as the two belonged to different traditions within the LDP – Abe being hawkish and Kishida being dovish – the fact was that they worked very well together. Kishida served as the longest foreign minister under Abe and without Abe’s support behind Kishida he would not have become prime minister.

So where is Japanese politics headed? It is back to the future. The LDP will remain in power, as the opposition forces are weak, divided, and in disarray. The likely scenario is that theLDP will continue to dominate national politics but be divided by intense competition among factions for the prime ministership and cabinet posts, thus threatening to revive thefrequent changes in leadership of the past. This is not ideal for Japan or for the world. But the good news is that Japan’s commitment to the concept of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific, its unwavering alliance with the US, and security and strategic ties with like-minded partners put in place by Shinzo Abe will continue including through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, regardless of who is prime minister.

Purnendra Jain is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Asian Studies at the University of Adelaide.

Banner image: Japanese PM Fumio Kishida attends Nagasaki Peace Memorial Ceremony - August 9, 2022. Credit: @JPN_PMO, Twitter.