Southeast Asian states have so far avoided choosing sides in the growing US-China rivalry, seeking the benefits of good relations with both. But Indonesian analysts Yohanes Sulaiman, Mariane Delanova, and Rama Daru Jati argue the region’s biggest power will struggle to maintain the strategic middle ground.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread havoc around the world one major casualty is the relationship between the United States and China. China, well aware of how its blunders in the early days of the pandemic undermined the image of a Chinese Communist Party that is competent and completely in control, has since been trying to shift blame to other countries, such as Italy and the United States.

In turn, the US, despite the partisan rancor of the presidential election, has managed to find at least a semblance of unity in projecting negative images of China. The new U.S. Secretary of State Tony Blinken, has echoed some of the Trump Administration’s more strident statements on China, declaring China’s policy in Xinjiang a genocide and suggesting Taiwan play a greater role around the world. That stance has obviously irritated Beijing.

It means a post-COVID-19 world will most likely be marked by growing distrust and discord between the world’s two biggest powers.

As the Sino-American relationship continues to deteriorate, the countries of Southeast Asia are likely face greater pressure to pick sides, given the strategic importance of this region to the great power rivalry.

While China’s influence with ASEAN members has been increasing due to its growing economic might, its support for regional autocrats, and its vaccine diplomacy, the region’s governments, and its peoples, remain wary of China as they harbour doubts about China’s intentions, especially in the South China Sea.

Still, the region as a whole does not want to choose sides. One reason is historic: Southeast Asia was literally a battleground for the superpowers during the Cold War. China supported communist insurgencies all over Southeast Asia, while the US, besides being seen as meddling too much, added fuel to internal conflicts by viewing them through the prism of the Cold War and injecting arms, as in the failed PRRI/Permesta rebellion in Indonesia. Not surprisingly, when Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, and Thailand decided to form ASEAN, one of the organisation’s key principles was nonintervention in other countries’ affairs.

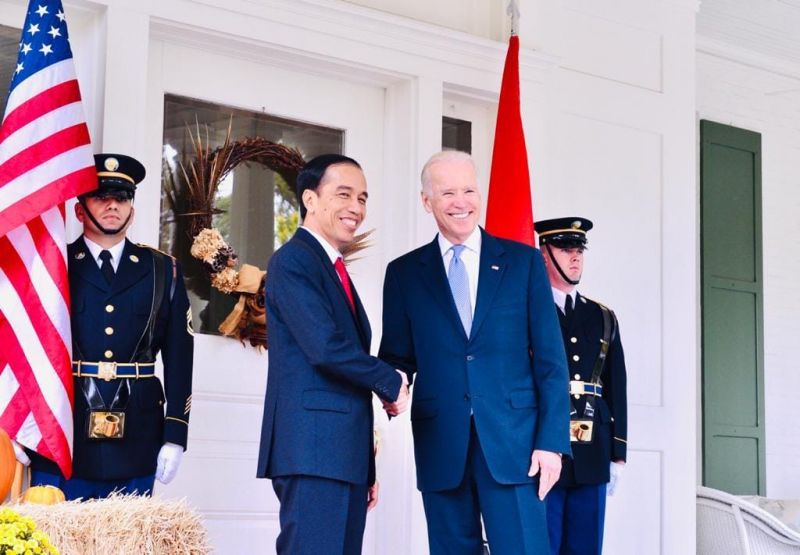

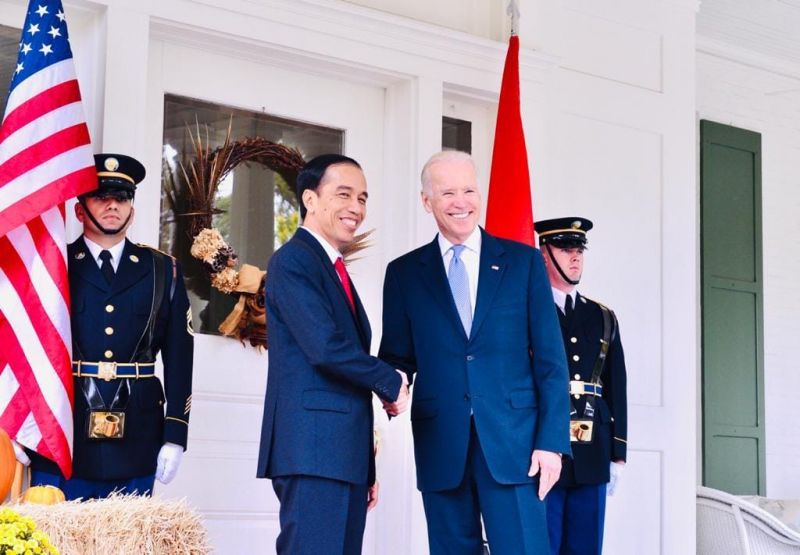

Indonesia is maintaining a balancing act – courting both the United States and China while attempting to not to take sides with either country. Image credit: @Jokowi, Twitter.

Another reason is material benefit: all of them want to maintain the status quo of enjoying the economic dividends of a healthy relationship with China — especially in view of the damage sustained to the economies of the US and Europe during the pandemic — while being able to rely on American strategic protection. A dispute with China would have dire economic consequences. Witness the current trade tensions between China and Australia, with China imposing tariffs on Australian barley, beef, coal, lobster, timber, and wine. With ASEAN countries becoming ever more economically dependent on China, it is clear they will be hesitant to issue an open challenge to Beijing.

Indonesia is trapped in this dilemma. It considers itself the leading state in Southeast Asia due to its size, population, resources, and strategic location on the world’s busiest maritime traffic routes. Its foreign policy has always had the goal of maintaining regional stability and preventing outside powers from gaining outsized influence that would challenge its leadership of the region.

As a result, it seeks to leverage its strategic importance by playing a mediating role in the region, managing the competing interests of outside powers, especially the US and China. Its aim is to ensure that no state will have too much influence on either Indonesia or the region.

Not surprisingly, China and the US have been vying for influence in Indonesia. China has offered its vaccine, delivering 1.2 million doses by December. The US donated ventilators and has approved the sale of advanced weaponry, such as MV-22 Osprey.

Despite those overtures, Indonesia has tried to steer a middle course. It has sought to avoid the risk of being entrapped in future US actions against China, especially in the troubled hotspot of South China Sea. At the same time, it has had to deal carefully with China, lest it become too dependent.

Given rising tension in the South China Sea between the US and China, however, Indonesia will have to guard against being inadvertently dragged into conflict. Already there are troubling developments, such as China’s passage of a law that allows its coast guard to fire on foreign vessels “if needed.” Although the law most likely is aimed at the US, it has caused acute discomfort among members of ASEAN. The Philippines’ retired Supreme Court Justice Antonio Carpio bluntly stated that China had rendered any Code of Conduct in the South China Sea “dead on arrival.” And Indonesia summoned the Chinese Ambassador to Indonesia Xiao Qian to stress Jakarta rejected the application of the law in Indonesia’s maritime zone.

Mountains in the Natuna Islands – an area of contention in the South China Sea. Image credit: Arielevis, Shutterstock.

Moreover, there are rising concerns within the Indonesian military over whether Indonesia is prepared for a conflict with China. In an unprecedented move, the December issue of the Indonesian Army Staff and Command School bulletin included an article that concluded that a Chinese attack on Indonesia’s Natuna Islands was imminent, claiming China had both the motive and the capability to launch such an attack from its bases in the Spratly Islands. During testimony to the Indonesian parliament, Vice Admiral Aan Kurni, the head of Indonesian Coast Guard, stated that China’s new law had increased the risk of conflict.

In all likelihood, Indonesia will have to rethink the viability of a strategic policy of equidistance between the US and China. It might need to consider which side is more accommodative of its interests in maintaining regional stability and align itself accordingly.

Yohanes Sulaiman is Lecturer in International Relations at Universitas Jendral Achmad Yani in Cimahi, Indonesia.

Mariane Delanova is Lecturer in International Relations at Universitas Jendral Achmad Yani.

Rama Daru Jati is an undergraduate student in International Relations at Universitas Jendral Achmad Yani.

Banner image: Indonesian Parliament, Jakarta - July, 2020. Credit: Bimo Pradsmadji, Shutterstock.

This article is adapted and updated from Yohanes Sulaiman, Mariane Delanova, and Rama Daru Jati, “Indonesia Between United States and China in Post-Covid-19 Bipolar World Order,” Asia Policy, Vol. 16, No. 1 (January 2021) pp. 155-178.