Haunted by History: Real Lessons from the 1930s

By Prof. Anthony Milner AM, Senior Adviser, Asialink

When Prime Minister Morrison last July announced a major upgrade in Australia’s war-fighting capability, he offered a bleak reflection on history. He admitted to regularly “revisiting” the years that lead to the “existential threat we faced when the global and regional order collapsed in the 1930s and 1940s”.

“When you connect both the economic challenges and the global uncertainty, it can be very haunting,” he said.

Our Prime Minister is wise to look back, including on the record of Australian governments of the day. The 1930s evokes powerful images – we endured the Great Depression and witnessed the rise of revisionist powers in Asia and Europe that challenged the global order. It culminated in the calamity of World War Two.

When we reflect on history we need to look past the background noise and static, to seek real lessons that might aid contemporary decision-making. Dismissing the historical record with such folk simplifications as ‘Domino Effects’ and ‘appeasement’ can be unhelpful – muddying our judgment.

During the pre-War years of the 1930s, Australia was governed by another electorally successful conservative administration, led by Joseph Lyons and including such prominent figures as John Latham, Richard Casey and Robert Menzies. Lyons won three successive terms between 1932 and 1939 – the years when Japan emerged to press its claims as Asia’s dominant power.

We know how that ended. But we might ask, how did conservative policymakers of that time perceive the strategic environment and act to secure Australian interests? Did they have a clear view of Australia’s capacity for independent action? What role did they see in Australia’s security for a Western ‘great and powerful friend’? And what were their views on how best to manage Japan as a rising power?

Although Australia sought to avoid war, and failed, the manner in which our leaders answered those questions and handled Australia’s international challenges might surprise some in the Coalition today. There was a desire to operate independently in the Pacific – and in its different initiatives the Lyons government reminds us that the conservative side of Australian politics has a serious heritage of positive engagement with the Asian region.

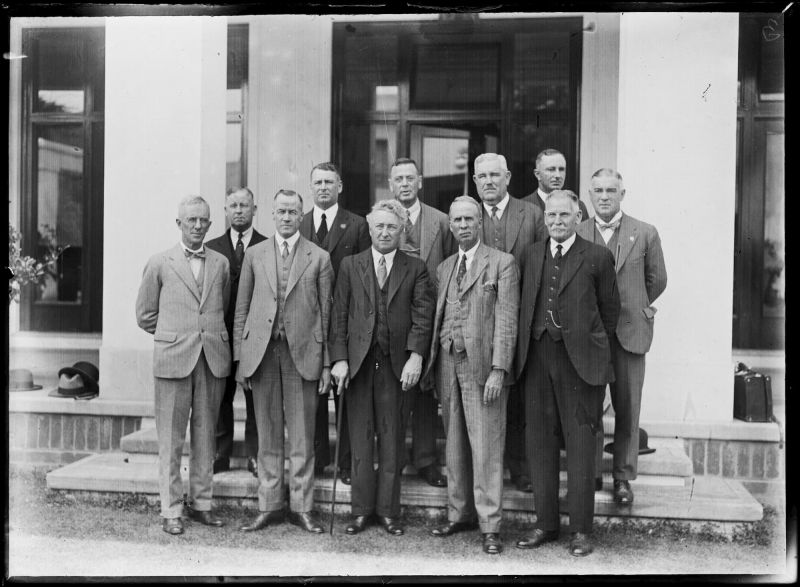

Prime Minister Lyons' (first row, centre) first ministry – January 11, 1932. Image credit: National Library of Australia.

The Lyons government valued Australia’s relationship with its ‘great and powerful friend’ – at that time, the United Kingdom not the United States. The ‘fear of abandonment’ – which Allan Gyngell describes as lying ‘deep in the history of European settlement in Australia’ – was also present in these years. There were doubts about the military capacities of the Singapore naval base and an anxiety that Britain might become too preoccupied with challenges in Europe to attend to Asian region issues.

There were fears, in addition, about entanglement as well as abandonment – about Australia being drawn into a European war which it did not favour. Gaining influence over London’s foreign policy was a priority – but often frustrating, even when it concerned Australia’s region of the world. The Lyons government acknowledged that British and Australian interests in Asia differed. Menzies, so famous today for his British sympathies, was one of those who felt the “British authorities [were] indifferent to the problems of the Far East and in particular to our own vital concerns to maintain friendly relations with Japan”.

One conservative response was to spend almost twice the amount on defence as a share of GDP as our government delivers today. There also was an insistence that Australia needed a Pacific outlook, or a ‘Pacific Policy’, to use the phrase preferred by Alfred Deakin – the early non-Labor prime minister who (as Menzies later recalled) laid down all “the foundational policies” of the Australian nation. Deakin had seen that such an outlook required Australia to act independently at times. He irritated the British government, for instance, when he invited the American Great White Fleet to visit to Australia in 1908.

In 1934, Lyons caused surprise in Britain when he sent an Australian Eastern Mission to the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, Vietnam, the Philippines, and China, as well as to Japan. Led by External Affairs Minister John Latham, Lyons explained that it was the first “official visit” by Australia to the region. In foreign relations, he said, what mattered was to “understand one another’s point of view”. The government also hoped to expand Australia’s trade with Asia.

Already some eleven per cent of Australian exports were going to Japan – a low figure compared to today’s export levels to China, but one factor in Australia’s desire to avoid conflict with Japan. Lyons and others in the conservative elite – more than their British counterparts – saw that to avoid war there was a need to make space for a growing Asian power. The Japanese, Lyons thought, might be allowed to “expand in their own area” – he, Latham and others were even willing to respect Japanese ambitions in Manchuria. Lyons argued the need to conciliate Tokyo “before any new alignments solidified into alliances.”

Another independent initiative into which Lyons put energy was the so-called ‘Pacific Pact’ – intended to be a pact of “non-aggression and consultation between all the countries of the Pacific”, and one embracing “a general declaration of economic and cultural collaboration”. Lyons and his colleagues lobbied for this with representatives from Japan, China, the Netherlands and France – and with President Roosevelt himself.

The Pact endeavour qualifies the view that conservative approaches to foreign relations in Australia emphasise ‘power and alliances’ while it is Labor that puts weight on ‘collective security and international institutions.’ This said, the proposal did not gain effective British support – which was one reason why the Lyons government decided Australia had to have its own diplomatic presence in the key capitals of the region. The first representatives to the United States, Japan and China were sent too late to help the Pacific Pact – but they were the pioneers of Australia’s diplomatic network across the Indo-Pacific.

Lyons, in his commitment to “international co-operation” referred often to the need to understand the perspectives of others. Some of those around him saw that this would be increasingly challenging with the decline of European empires. Conservative politician and diplomat, Frederick Eggleston – who had a philosophic interest in cultures or social ‘patterns’ – saw “the East awakening” and noted that British officials were too inward-looking to comprehend this. Eggleston was impressed by the Asian intellectuals he met at international conferences and believed Australians could benefit from their ideas.

A Lyons academic advisor, A.C.V. Melbourne, took a similar approach – suggesting it was crucial for Australian trade officials to establish close relations with “people of Japanese and Chinese race rather than with foreign residents.” Australia, Melbourne said, needed to see itself not as European but as a ‘Pacific country’ – and he wondered how far Britain would assist Australia in an Asian war. Eggleston and Melbourne would be horrified to learn of the decline of Asian studies knowledge in Australia today.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison announces the 2020 Defence Strategic Update, Canberra, Australia – July 1, 2020. Image credit: @DeptDefence, Twitter.

We should not draw too literally from history to understand contemporary events. The international rules-based order we have today was then less elaborate. The existence of nuclear weapons now affects the calculus of war. Our economies were less deeply enmeshed. All this should help mitigate the risk of repeating the disaster that followed the economic and strategic upheaval of the 1930s.

But conservative policy-makers of that time appear to have had a clearer view of the need for independent Australian action than they do today. They were wary of over-reliance on a Western ‘powerful friend’. The Lyons government also saw it as realistic to accept that a dynamic Asian power, no less than a rising Western power, could be expected to demand greater elbow room in the global order.

Are we being as realistic today about China’s growing role? Apart from enhancing our military capacity, this might be one lesson to contemplate from the 1930s.

Professor Anthony Milner is International Director of Asialink, University of Melbourne.

Banner image: The Australian ship HMAS Ballarat participates in Exercise Malabar operations with regional defence partners India, Japan, and the United States – November 18, 2020. Credit: Defence Australia.

A version of the article was first published in The Australian on January 25, 2021.