Modi, Morrison and the Dragon in the Zoom Room

By Tanya Spisbah, Founder, Strategic Sustainability

While a number of areas for cooperation will be discussed when Scott Morrison and Narendra Modi connect via videolink for the Australia-India Virtual Leaders’ Summit, the strategic context in which the talks take place is paramount. China-US tensions will be top-of-mind for both leaders.

Neighbourhood Watch – the Quad and China

China is the dragon in the Zoom room. Although both Australia and India rely on trade with China, China’s increasing aggression in the South China Sea, and more broadly, makes it difficult to strike a balance between economic and strategic policies.

The Quadrilateral Security Initiative (or “Quad”, as it is known), originally founded by Australia, India, Japan and the United States to address the impact of the 2004-05 Indian Ocean tsunami has evolved into a mechanism for strategic cooperation. Australia, formerly against China ‘containment’, left the Quad and has re-joined in its quest for China ‘balancing’.

The Quad met in March to discuss COVID-19 management in the region, including the geopolitical impact of the pandemic on the Indo-Pacific. Each of the founding members has a complex relationship with China. Each has China as its number one trading partner; each has attempted to balance China’s rising power while attempting to preserve positive relations, and has found this a difficult balancing act, with tensions escalating in the last month.

The US, under President Donald Trump, has retreated from longstanding policies of economic engagement and adopted an anti-China stance. Trump has triumphantly careened from an ‘all time high’ in China relations in January 2020, to an all-time low, calling coronavirus the worst attack China has launched on the US and the world. He has upped the US military presence in the South China Sea and has stated he is exploring decoupling the US and Chinese economies altogether. Despite their heavy economic interdependence, neither the US nor China is backing down, with murmurings of an emerging ‘Cold War 1.5’.

Japan has tensions with China too. COVID lockdowns prevented President Xi making a State visit earlier this year were seen as a potential ice-breaker to celebrate a thawed relationship. Instead, US loyalties combined with concern for its own economy has led Japan to spend significant sums repatriating China-based businesses to Japan or to other markets, irritating China. These add to old territorial disputes in the East Sea and lingering grievances over Japan’s wartime record.

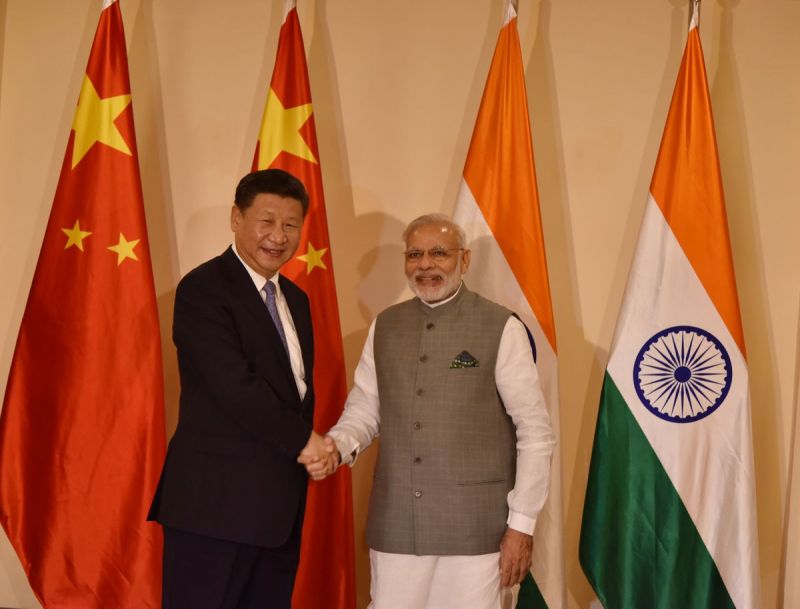

An increased Chinese military presence in Ladakh has escalated tensions between India and China. Image credit: Narendra Modi, Flickr.

Australia’s relationship with China is unravelling quickly. After decades of friendship, tensions have risen in recent years over Australian responses to Chinese investment and ‘foreign interference’. The relationship is now at a historic low, with China taking umbrage at Australia’s call for a World Health Organisation (WHO) investigation into the origins of the coronavirus. The call was co-sponsored by 130 WHO members and passed by consensus on 19 May, yet China has retaliated by imposing meat bans and 80 percent tariffs on Australian barley in recent weeks.

Now India joins these other members of the Quad in experiencing increasingly fraught relations with China. Although China is undoubtedly a significant partner, the border war of 1962 is never far from memory. The recent increase in Chinese military presence along the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh has escalated tensions, with high level military talks to take place later this week to address the issue. China and India would benefit from peaceful relations – as two populous neighbours, with ancient civilisations, large economies and contemporary geopolitical heft. However, India’s competitiveness and China’s constant border bullying and wooing of strategic neighbours are constant points of friction.

The coercion tactics employed by both the US and China underscores the need for strengthening cooperation between other polar-balancing nations and a restoring of respect for institutional rules once reformed.

G7 to D10

Trump’s latest strategic gambit has been to suggest broadening the G7 to include Australia, India, South Korea and Russia to reflect the realities of global influence today. Yesterday, both Morrison and Modi accepted Trump’s invitation to this year’s G7 meeting.

Although French President Macron extended the same invitation last year, Australia and India need to weigh the strategic costs and benefits of a permanent broadening of the G7 membership. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has suggested a ‘D10’ – the G7 plus 3 to make up a group of ‘10 Democracies’, excluding Russia. However, it would be difficult to interpret the move as anything other than a China exclusion tactic by the US. That would risk undermining the G20.

Australia and India have sought to preserve their respective relationships with China despite difficulties. A formal G7 expansion may risk each being party to another China exclusion club, potentially becoming pawns in a Trumpian manoeuvre. The consequence could be tipping multipolar powers toward a bi-polar axis, with nations forced to choose between China or the US, reminiscent of another cold war. Relations with the United States pose their own issues, with Trump taking an anti-global stance while in crisis on multiple fronts domestically.

For now, the Quad allows for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific and the G20 allows for discussions of global issues with a broad representation. Modi and Morrison might discuss the strategic merits of permanent membership of the world’s G7 rich club versus the costs.

Opportunities for multilateral cooperation

India sees the 21st Century as its own and has increasingly asserted itself in multiple multilateral fora. In March, Modi called for extraordinary meetings of the G20 and of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). Then in May, he gave his first ever address to the Non-Aligned Movement.

Institutionally, India has assumed the Chair of the World Health Executive Board for the next three years and has been active in calling for the strengthening of WHO investigative powers.

It is likely that India will be voted as a non-permanent member to the UN Security Council for 2021-2022, overlapping with India’s host year of the G20 in 2022.

India has also taken on institution-creation in recent years, founding the International Solar Alliance (ISA) and established the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure. Australia is a founding member of both organisations and finances a position in the ISA Secretariat.

Modi and Morrison have taken different approaches to multilateralism, with Modi calling for a ‘new humancentric multilateralism’ while Morrison has warned of the effects of ‘negative globalism’. However, both are committed to international institutional reform and have historically been committed multilateralists. A new global order is emerging and this bilateral is an opportunity to identify points of convergence in its development.

Bilateral ties

India is seeking support for its emergence as a global leader in the 21st Century. It is eager to develop greater capability in technology, connectivity and trade and leadership on climate change – the indicators of power in the 21st Century according to Foreign Minister Jaishankar.

Modi has launched a new idea of India: Atma Nirbhar Bharat—Self Reliant India—which he reiterated at India’s largest trade conference yesterday, celebrating the 125th anniversary of the Confederation of Indian Industry. Instead of autarky, Modi is said to be establishing India as robust and internationally integrated as a provider, not a recipient, of critical resources for 21st century power.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison has remained upbeat about the Australia-India relationship, despite the current challenging global circumstances. Image credit: Asialink.

Australia could be a valuable partner to a self-reliant India. It has the critical minerals that support India’s ambitions as a renewable energy leader for battery storage and solar panels. It has shared cybersecurity concerns that might support India as a leader on Information and Communications Technology, cybersecurity, the Internet of Things and 5G mobile – pervasive technologies that will govern healthcare, agriculture, e-commerce, smart energy and transport sectors.

Australia is also a technology partner in health and medicine and could enable India to develop from being the world’s pharmacy to broader strengths in vaccine production, medical devices and digital health expertise.

The bilateral Summit will focus on cooperation that will make each country stronger in the region – economically and geopolitically. Given India’s decision not to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) last year, restarting discussions on a bilateral trade agreement could be of mutual interest. Australia also looks forward to the announcement of India’s ‘Australia Economic Strategy’, which would map economic complementarities and opportunity over the coming decades. Strategically, escalating the ‘two-plus-two’ dialogue of foreign affairs and defence officials from departmental secretary to ministerial level would boost strategic cooperation. Similarly, the signing of the Logistics Support Agreement providing reciprocal access to bases and ports would significantly advance defence cooperation.

India’s ambitions are justifiably large. The Summit comes at a difficult time, with now over 200,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19, millions of migrant workers returning back to villages potentially undetected and New Delhi’s borders closing this week in response to a spike in infection numbers.

Despite the grave global circumstances, each Prime Minister remains upbeat, exchanging good-humored messages on Twitter with Morrison baking ‘Scomosas’ for a Modi future sampling. Perhaps a successful bilateral relationship will have Modi posting images of Vegemite toast. Undisputedly, Australia and India are crucial anchors in the region, and their relationship will continue to shape a shifting Indo-Pacific.

Tanya Spisbah is Director of the Australia India Institute in Delhi and former Australian diplomat to India.

Banner image: Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi interacts with students at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India - February 22, 2016. Credit: Narendra Modi, Flickr.