Is Japan Returning to the Revolving Door Leadership?

By Purnendra Jain, Emeritus Professor, Department of Asian Studies, University of Adelaide

The adage that ‘a week is a long time in politics’ does not adequately capture the speed of events that changed Japan’s political scene within hours on Friday. Until the late afternoon of the previous day, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga was set to run for the presidency of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in a ballot scheduled for 29 September. A win would have allowed him to continue as Japan’s prime minister and lead his party to a general election, which must be held by late November.

But the political landscape of Nagatacho, the seat of Japanese politics, changed dramatically with Suga’s Friday announcement that he won’t contest the party leadership and would thus step down from the prime ministership.

The party president assumes the prime ministership as the LDP, together with its junior ally the Komeito, holds a solid majority in the lower house of parliament.

Why Suga made his sudden decision is a mystery. Did he jump or was he forced out? Either is possible.

Suga announced his decision to stand down following an unscheduled meeting on Friday morning with Toshihiro Nikai, the powerful LDP secretary general and faction leader, who was the first to endorse Suga’s bid for re-election. But what happened in the room is hard to guess. Apparently Suga did not even consult former prime minister Shinzo Abe, who was the key to Suga’s prime ministership following Abe’s sudden resignation in August last year.

Certainly, Suga’s popularity was heading south for months. By the end of August, his cabinet’s approval rating, according to one newspaper poll, was in the low 30s while its disapproval rate was in the high 50s, largely a result of dissatisfaction over the poor handling and high caseload of coronavirus following the Tokyo Olympic Games and slow rates of vaccination. And yet Suga had decided to run for the presidency, as he thought he had the support of top party figures such as Nikai, Finance Minister Taro Aso and Abe.

Suga’s fate was sealed by electoral losses in a number of parliamentary by-elections and local elections in preceding months, including the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly elections in July, where the LDP failed to gain a majority. These elections are not an accurate barometer of the national political mood. But they do show trends.

One local election in particular – for mayor of Yokohama, a city of some 4 million people neighbouring Tokyo, and Suga’s home electorate – might have ensured the Prime Minister was running out of time. In a fiercely contested and nationally watched election, the high-profile LDP candidate Hachiro Okonogi, a former Suga minister, lost to opposition-backed candidate Takeharu Yamanaka

Despite these losses and his own sagging popularity, Suga showed no signs of withdrawing from the race. He considered some quick fixes to rebuild his public image, promising to renew the LDP’s executive ranks and carry out a cabinet reshuffle. But he soon retreated in the face of staunch opposition by the party old guard.

As of 3 September, the only declared challenge to Suga’s leadership of the LDP was from the former foreign minister Fumio Kishida. Other names were thrown into the mix, such as Sanae Takaichi, a conservative who would be Japan’s first female prime minister. She reportedly has Abe’s backing. Taro Kono, who has overseen Japan’s vaccine rollout, is another potential challenger. Two others — Shigeru Ishiba, a former defence minister, and Seiko Noda, another potential female contender, Abe critic, and former internal affairs minister — are considered outside chances.

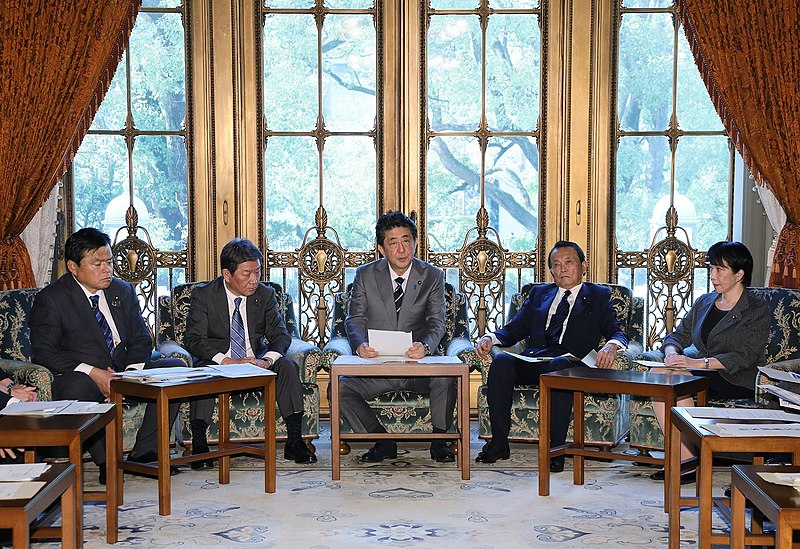

Sanae Takaichi, far right of image, is a former member of the Abe cabinet and is considered a contender in the LDP leadership race. Image credit: Prime Minister's Office of Japan.

But the cumulative effect of losses in several local elections, declining public support, a rising number of COVID cases, a looming general election and above all, internal party discontent, especially among the LDP’s young generation might have been too much for Suga to handle. He had reportedly confided in his meeting with Nikai that he had ‘lost energy’ (kiryoku o ushinatta) and that there were people ‘squirming in the back’.

Now that Suga has joined a long list of revolving-door prime ministers (before Abe returned to power for the second time in 2012, he was preceded by six prime ministers in roughly six years) more candidates will come forward. With three weeks to go till the ballot, there is still considerable uncertainty over who will run. Taro Kono has already announced his candidacy, although his faction boss, Taro Aso, is yet to give Kono his blessing. Others are taking internal soundings of their support. There has even been some twitter speculation about Abe returning for a third time!

Public opinion favors Kono, Ishiba and Kishida in that order. But the selection of an LDP president is not purely a popularity contest. Factional bosses and backroom manoeuvres make or break a party leader. Suga was not the most popular choice with the public when he was elected party president last year.

The LDP operates on factional politics. The party has currently seven factions and the largest is the Abe-Hosoda faction with Aso’s faction in number two place. Together with the Nikai faction they are able to influence the outcome of the presidential election, as they did last year.

But one additional factor complicates the outcome – the inclusion of a rank and file vote. Rank and file and LDP parliamentarians will each have 383 votes. How party members vote will matter. Some suggest that many of the new generation of party members and parliamentarians are driven by popularity of leaders as reflected in public opinion polls, and want to shun factional machinations. This could open the door to a surprise, like the election of Japan’s first female prime minister.

One silver lining for the LDP is a weak and divided opposition. Most voters still largely prefer the LDP over the largest opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party. With a new leader in place just before the election, many in the party believe the LDP’s electoral prospects improve significantly.

But the big question is whether the new leader will possess the necessary skills to keep the party together and have the political acumen to survive as prime minister. Alternatively, will Japan once again enter a period of political instability with frequent changes of prime minister?

The task and challenges ahead for the new leader will be immense. He or she will need to convince voters that the party and government will stay on top of the coronavirus situation and make policy that would reinvigorate the economy.

It is not clear at this stage who will succeed Suga and how efficiently the new leader will tackle the immense domestic challenges – not to speak of the strategic challenges that face Japan amid the relentless rise of an assertive China and its intensifying competition with the United States, Japan’s ally and closest partner.

Purnendra Jain is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Asian Studies at the University of Adelaide.

Banner image: Japanese PM Yoshihide Suga speaks to press on "Disaster Prevention Day", Tokyo, Japan - September 1, 2021. Credit: @sugawitter, Twitter.