Indonesia, Frank and Fearless

President Joko Widodo at a Jakarta rally in 2014. Photo by Uyeah

Australia’s relationship with Indonesia deserves the highest level of priority, but too often this slips off the radar of corporate decision makers. With the Indonesian general election in 2019 just around the corner, and a new bilateral FTA on the horizon, it is timely to take stock of the opportunities and challenges.

This analysis – drawing on insights from a recent “State of the Nation” discussion forum convened by Asialink Business with leading Indonesia experts – is designed to give Australian companies the frank and fearless information they need to navigate the complexities of doing business in Indonesia.

A 2018 Snapshot

Taking a quick snapshot of Indonesia’s economy, there’s a lot to like, with the country’s growth rate sitting at roughly five per cent for the past five years. While this hasn’t hit the heights of neighbours Vietnam, China, India and the Philippines, this steady growth is certainly nothing to sneeze at. Indonesia also has one of the fastest growing middle-class populations in the region and a very large consumer base.

‘Indonesia spends money on the right stuff,’ says consultant Douglas Ramage, who previously held roles with the World Bank, the Asia Foundation and AusAID.

Health, education and infrastructure get the lion’s share of state funding, while Indonesia’s military budget is comparatively small. This is a great sign for Indonesia’s development. But – as Indonesian Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati has underlined – the impact of government spending could be significantly improved.

The next Presidency?

We’re now four years in to President Joko Widodo’s tenure – and his achievements need to be recognised. Initially characterised as a mere small-town mayor, he has clearly proven himself a sophisticated politician capable of making policy inroads. He is served well by his Cabinet, which includes some notable technocrats. Early in his term, Widodo (popularly known as “Jokowi”) took the electorally brave but necessary step of removing fuel subsidies and pushed the billions of dollars into social welfare programs.

For Ramage – the three big achievements of Jokowi’s presidency to date have been the funding of the national health insurance program, the creation of education subsidies for those in need, and the massive increase in infrastructure spending.

As we approach the 2019 national elections, it is worth reaffirming that Indonesia does elections very well. It is a largely peaceful, multiparty democracy that has some of the highest rates of voter participation in the world.

That said, the upcoming election campaign takes place against the backdrop of rising intolerance. Recent years have seen further terrorist plots, the prosecution and imprisonment of the Governor of Jakarta for blasphemy and attacks on the LGBT community by hard-line conservatives – all of which have the potential to undermine Indonesia’s stability, and damage the quality of Indonesia’s democracy.

After being apparently set on Mahfud MD, former well-regarded Chairman of the Constitutional Court and former Minister of Defence, as his vice presidential running mate, Jokowi faced criticism from within his party and has now announced the highly conservative 75 year-old Ma'ruf Amin. It appears likely that this shift brings with it the chance of a successful Jokowi ticket becoming more socially conservative and a further rise in economic nationalism.

Professor Vedi Hadiz suggests the current movement to “defend Islam” in Indonesia is part of a narrative that Muslims are poor, oppressed and marginalised within a rapidly changing nation.

‘The economic and the religious narratives are connected,’ says Hadiz. To understand where this movement is heading, we need to understand Indonesia’s remarkable demographics and its labour force.

Unpacking the Demographic Dividend

Indonesia has a young population and a low proportion of dependant adults. This is known as a demographic dividend, or surplus, and it is a great asset for both the nation and the business community.

Indonesia has a very large labour force, which is also considerably better educated than the generation before it. This is a generation that is interested in finding alternative ways of doing things. It is a generation that is pioneering very exciting new territory in the emerging digital economy, including film, animation, design and other tech startups.

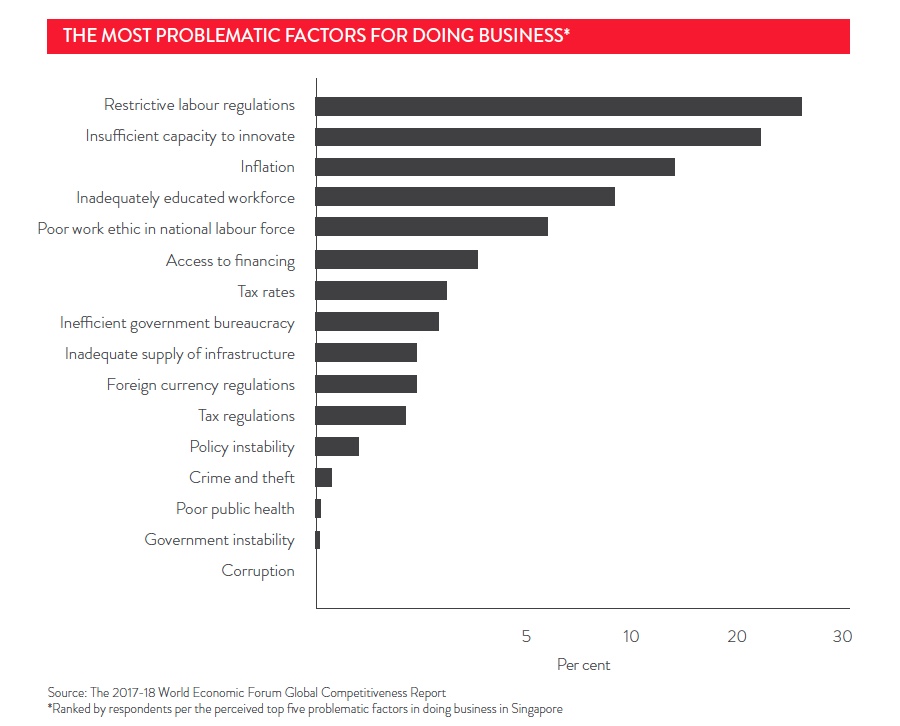

However, it isn’t all smooth sailing ahead. Despite the significant progress with quality of education, Indonesia still has an uncompetitive labour force when compared with most of Southeast Asia. Ramage cited a UNICEF study that found 55% of 15-year-old students are ‘low achievers’ in reading, which can functionally translate into a large proportion of the workforce being unable to read a factory manual, for instance. This ‘functional illiteracy’ is striking when compared with Vietnam, where the figure was just 12%.

There are also other challenges in the labour space. While the official unemployment rate is roughly six per cent, Hadiz believes that the big issue is underemployment, which may be as high as 35%. Evidently, this presents opportunities for business, but it also reflects serious structural problems for the economy.

As local businesses increasingly choose short-term contracts or outsourcing, there are looming conflicts with trade unions. The other labour market factor worth consideration is the fragmented union movement.

'It’s almost impossible to count all the unions right now in Indonesia,’ says Hadiz. ‘It is a chaotic and fragmented movement that has no overarching guidance.’

Working within Economic Nationalism

Economic nationalism is still very much present in Indonesia. The government is clearly favouring a state-centric model of investment, and this recent ‘double down’ has led to the perception that state-owned enterprises are taking a disproportionate share of investment and business opportunities. For the big foreign investors, the message is clear: if you want to be part of the big projects, you need to go through the state. While this might seem self-defeating, it is similar to the approach taken by Brazil, with the logic being that our market is so big you can’t afford not to come to us.

Adding to this complexity is the current legal and contractual uncertainty. The Indonesian judiciary ranked 145th out of 190 countries according to the World Bank. On the business front, the high-profile 2013 court verdict against a local employee of US energy giant Chevron sent shockwaves across the business community.

What this means, according to the experts, is that foreign businesses need to think innovatively about ways to work within the constraints. For instance, in the tech space when the Indonesian authorities compelled companies to involve local providers in their supply chains, Apple promptly worked with the government to establish one of only three Apple Developer Academies globally in Indonesia.

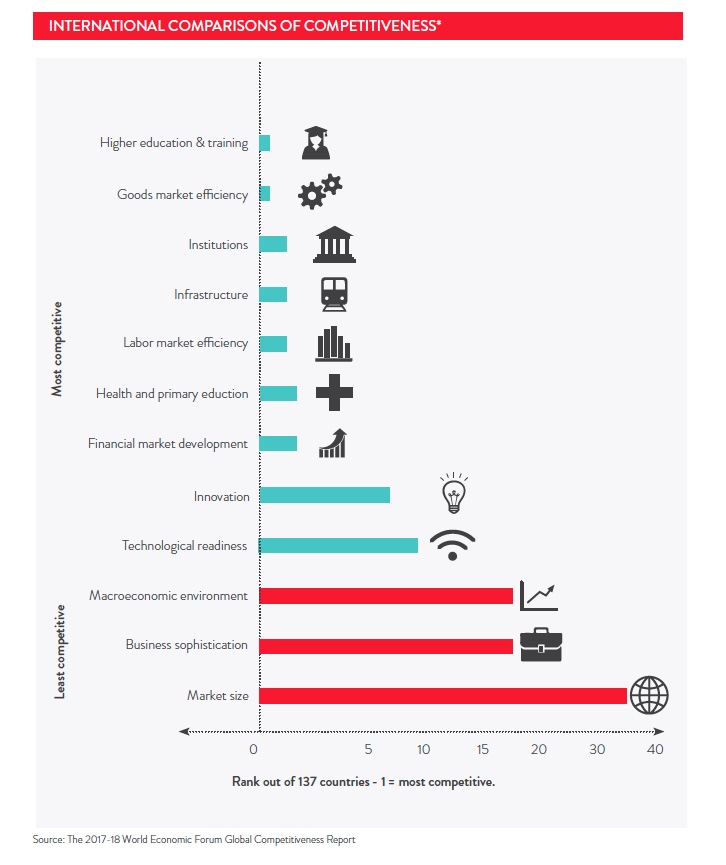

There are other positive signs. One standout figure is that Indonesia has gone from ranking 120th in the World Bank’s 2014 ‘Ease of Doing Business’ ratings, to 72nd in 2018. Likewise, Business Confidence and Competitiveness indices both continue to rise. The current climate suggests that success varies from sector to sector. Mining, for instance, is currently a complicated industry, whereas in technology, caps on foreign direct investment for tech startups have recently been lifted.

The other positive development for Australian business is the very recently concluded Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (IA-CEPA). The Australian agricultural sector is set to benefit immediately, along with steel exports – and tariffs will also be removed from a long list of manufactured goods from 2020.

Take Advantage of the High-Level Relationship

We don’t speak enough about the quality of relations between current Indonesian and Australian leaders. As former Fairfax correspondent to Indonesia, Jewel Topsfield, recalls, the bilateral ties were unquestionably strained by the execution of convicted Australian drug smugglers in 2009. However, by November that same year the stroll of then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and President Jokowi through a garment market at Tanah Abang created a strong personal bond between the two leaders. It went viral on social media, and sent a bolt of electricity through the relationship, a momentum that both sides will hope continues into the Morrison Government.

We can take heart in knowing that there is a strong showing of Australian experience and understanding among Indonesia’s cabinet. This rich Australian experience within Indonesia’s ministry should evoke some self-reflection in Canberra. We should be disappointed that none of the Australian ministry is able to speak Indonesian – and we should be doing everything we can to tackle the core reasons for this. Which leads us to education.

Prioritising education for P2P

‘The whole tide needs to lift,’ says Joel Backwell, from the Victorian Department of Education, who leads some of Australia’s most innovative education initiatives .

More than 65,000 Victorian students choose Bahasa Indonesian at school, but, Backwell laments this is not translating into language capability at the senior levels of government or business.

Indonesia is a significant and growing international education market for Australia. While there is room to grow, pleasingly we are beginning to see more reciprocity as larger numbers of young Australians pursue study or work placements in Indonesia. Under the New Colombo Plan (or NCP) the Government has already sent more than two thousand young Australians to Indonesia (the most of any country), and over 40,000 across Asia. This is precisely the kind of investment required for the next era of Indonesia-Australia business ties to be successful.

Australia’s economic ties to Indonesia and the region will be less and less dominated by mining and resource extraction in the future as our services and digital trade continue to grow. That will require more boots on the ground in the region and deep experience and understanding and experience of language and culture. The people-to-people relationships, especially in education, between Australia and Indonesia will play a crucial role in creating that understanding.

There are incredible stories to be told in business, in social entrepreneurship, in education and the arts. We need to keep celebrating and supporting these relationships, because they’re our future.

Penny Burtt is the Group CEO of Asialink. This article first appeared in Access Asia, the monthly publication of AustCham Singapore.

The insights in this article draw on a discussion forum with Dr Douglas Ramage Managing Director for Indonesia, BowerGroup Asia, Professor Vedi Hadiz, Asia Institute, The University of Melbourne, Jewel Topsfield, National Correspondent, The Age, Joel Backwell, Executive Director, Victorian Department of Education and Training.

Asialink business thanks its event partners, Herbert Smith Freehills and the Australian Indonesia Business Council.

More information on doing business with Indonesia: asialinkbusiness.com.au/country/indonesia