The Rise of Video Art in East Asia

Refocusing on the Medium: The Rise of Video Art in East Asia

The exhibition Refocusing on the Medium: The Rise of Video Art in East Asia at OCAT Shanghai, assembled 25 works from key protagonists in video art from Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and mainland China. The show opened with a projection of Nam June Paik’s TV Buddha (1974/2002) a live-stream of the physical work from the Nam June Paik Centre in South Korea displayed the threshold of the exhibition, which was simultaneously broadcast back to audiences in Korea adjacent to the physical work. The intimation of proximity as facilitated by new media technologies that is exemplified in this display, which collapses the remote into the here and now, is an apt starting point for an exhibition that aims to construct a claim for video as the first truly global contemporary medium, while also elucidating the foundational role of East Asian artists within this global art panorama. Given that the condition of contemporaneity is characterised by a relative immediacy to the rest of the globe; a dilation of our awareness to encompass a multiplicity of other lives and localities unfolding simultaneously and yet disjunctively from our own, video is then exemplative as both product and producer of this tendency, as generative of globalisation and as a medium able to depict its effect. It is this particular quality – the capacity to dislocate and re-present time and space which is the province of new media art alone – that marks video as truly contemporary in nature [1].

Installation view of Refocusing on the Medium: the Rise of East Asia Video Art, 2020, and Nam June Paik’s TV Buddha, 1974 (2002). Image courtesy of OCAT Shanghai.

A collaboration between MAAP (Media Art Asia Pacific), Brisbane and OCAT Shanghai, Refocusing on the Medium draws on MAAP’s director Kim Machan’s doctoral research to refute a narrative that continues to centre the output of Euro-North America as vanguard while positing the activities of its colleagues in the rest of the world as relationally belated, in video as well as contemporary art history in general. Refocusing on the Medium evidences the erroneous nature of such a claim, pointing not only to the fundamental role played by of a number of artists from East Asia in constructing a new global aesthetic and conceptual language of video, but furthermore evidencing the manner by which the artists included in this exhibition were often in explicit and reciprocal dialogue with both their Euro-North American contemporaries and the global art historical canon; creating works that are clearly internationalist in their language, points of reference, and ambition. Shigeko Kubota’s video sculpture Duchampiana: Bicycle Wheel One (1983-1990), for example, takes Duchamp’s first recognised ready-made Bicycle Wheel of 1913 and amplifies its intimation of movement through the installation of a small video monitor between the spokes of the wheel on which natural and synthetically coloured footage of the Japanese countryside is screened. Katsuhiro Yamaguchi’s Las Meninas (1974-75)similarly elaborates Diego Velázquez’s canonical 1656 deconstruction of modes of visuality in painting, extending the work’s sightlines into the domain of the gallery environment through the use of a CCTV video installation which implicates patrons within the work.

Installation view of Katsuhiro Yamaguchi’s Las Meninas, 1974-1975. Image courtesy of OCAT Shanghai.

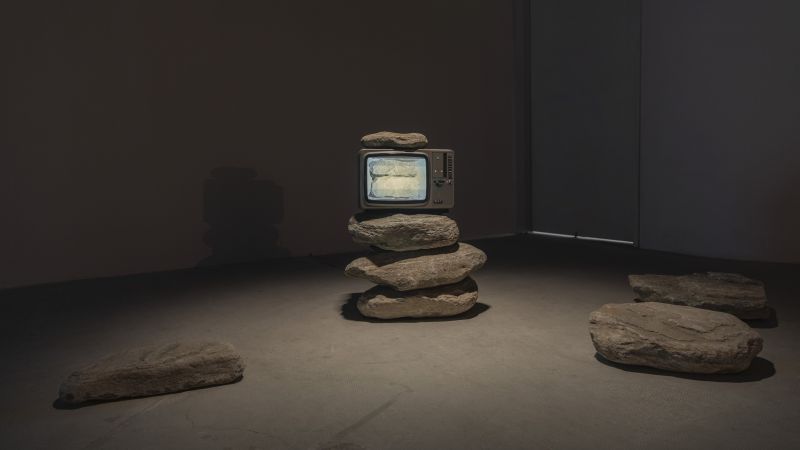

It is worth noting that the cultural non-specificity of video as a medium, arriving absent of any particular cultural baggage, does not necessitate a corresponding cultural homelessness. Works remain tethered to localised valences that may not retain fully legibility as an artwork circulates globally [2]. Art Historian Joan Kee, for example, has noted that the piled stone cairns of Park Hyun-ki’s Untitled (TV Stone Tower) (1979-1982)and Untitled (TV & Stone) (1984/2020) take on a particular shamanistic connotation in the Korean context, where they are prevalent [3]. Similarly, the disorientating affect of Ellen Pau’s Recycling Cinema (Viewing Room) (2000) offers a phenomenological representation of Hong Kong’s anxiety during the handover years leading up to and around 1997, suspending viewers (as the handover did Hong Kong’s residents) in a state of anticipation without resolution. Although many artists early to the domain of video were aspirational about its capacity to facilitate global connectivity (notably Nam June Paik), they were of course still operating from within a culturally inflected locality. Scrutiny of this duality seems to have been lost somewhat here to the aspiration to construct a claim to the global.

Installation view of Park Hyunki’s Untitled (TV & Stone), 1984. Image courtesy of OCAT Shanghai.

As suggested by its title, Refocusing on the Medium is interested in drawing our attention to the particular material qualities of video as medium. The selection of works narrate a period of experimentation that occurred with the adoption of the medium at staggered intervals across the region (in Japan from 1968, Korea 1978, Taiwan 1983, Hong Kong 1985, and mainland China 1988) subsequent to the commercial availability of the Sony Portapak portable video camera from 1965. As well as video’s capacity to collapse, distort and/or dislocate time and space, these qualities include the production of ambivalence between illusion and reality; the liveness of the medium; and its capacity to implicate the body within the environment of the work via a technological-physiological feedback loop. All of these tendencies are represented within the exhibition. Works by Wang Gongxin, Park Hyunki and Kim Kulim embed video footage of objects within, or adjacent to their physical correlate (timber, stone, a light bulb) to engage the differentiated qualities of presence/absence, time/timelessness and stillness/movement in the object and its pre-recorded representation. Takahiko Iimura’s This is a Camera Which Shoots This (1980), in which two tripod-mounted cameras record each other simultaneously from opposite sides of a room and reverse the signal to live-stream footage of themselves to a nearby monitor, illustrates the immediacy of CCTV, with the closed-circuit loop constructing the ‘this’ of the camera as both subject and object of the camera’s gaze. In her unedited video performance Etang de Vaccarèes (1985) Soungui Kim inhabits the camera as a bodily appendage, opening and closing its aperture over a body of water in synchronisation with her own breath.

Installation view of Takahiko Iimura’s This is A Camera Which Shoots This, 1980. Image courtesy of OCAT Shanghai.

Many works are highly sculptural, a spatial quality that is supported by the curation of the show which resists the invitation to spectacularisation extended by OCAT’s large, industrial spaces (typical of large-scale contemporary art galleries in China) and instead pursues a sparse installation to give works ample space to exert their presence as sculptural objects. There is no ‘black box’ screening room in which an artwork is detached from the gallery environment, a display choice so evocative of the cinematic experience and its attendant suspension of reality.

Refocusing on the Medium is a node in an ongoing dialogue and artistic exchange between MAAP and OCAT Shanghai, where Zhang Peili is the Executive Director, a relationship which has seen a number of collaborations in recent years [4]. A 2017 Asialink Residency allowed Machan an extended period in Shanghai to develop the project and deepen connections with the OCAT Shanghai exhibitions team, an experience that she suggests “undoubtedly strengthened the foundations of, and commitment to the exhibition that persevered against the odds in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and deteriorating Australia-China diplomacy [5].” The outcome has been an exhibition that successfully refocuses our attention on the central attributes of the video medium, surveying a group of artists from across the region who each display an acute sensitivity to the particular spatial, temporal, textural and conceptual qualities of video, and constructs a meaningful claim to their significance in the construction of a global contemporary discourse.

Cover image: Installation view of Park Hyunki’s Untitled (TV & Stone), 1984. Image courtesy of OCAT Shanghai.

Notes:

[1] Even prior to the advent of the internet, video technology, increasingly accessible and affordable in the last few decades of the twentieth century, marked a new era of possibility for international collaboration, communication, and exhibition. Curator Kim Machan recalls the stack of individual VHS tapes, mini-DVD cassettes and CD-ROM discs posted to her from Chinese artists for the 2000 arts festival of MAAP held at the Brisbane Powerhouse Centre for Live Arts. This portability (even in a limited sense compared to today’s standards) allowed artists eager to be exhibited overseas to realise this ambition. (Kim Machan, “On Curating Media Art between China and Australia since the 1990s,” in Zhang Peili: From Painting to Video, ed. Olivier Krischer (Acton ACT: ANU Press, 2019), 129.)

[2] David Teh, Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary (NUS Press, 2017).

[3] Joan Kee, “The Image Significant: Identity in Contemporary Korean Video Art,” Afterimage 27, no. 1 (August 1999): 8.

[4] This collaborative relationship most recently saw the exhibition LANDSEASKY: Revisiting Spatiality in Video Art (2014-15) which toured OCAT Shanghai; Artsonje Centre and five commercial galleries across Seoul; Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou; Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane; and the National Art School Gallery, Sydney

[5] Email correspondence with the author. 7 May 2021

OCAT Shanghai, 27 December 2020 – 21 March 2021

Artists

Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, Nam June Paik, Yoko Ono, Keigo Yamamoto, Kim Kulim, Takahiko Iimura, Shigeko Kubota, Park Hyunki, Soungui Kim, Wang Gongxin, Ellen Pau, Chen Shaoxiong, Geng Jianyi, Zhu Jia, Yuan Goang-Ming

Curator

Kim Machan (Director, Media Art Asia Pacific)